Velocity vs Capacity vs Load: An Analytical Comparison for Engineers

An analytical, accessible comparison of velocity, capacity, and load across engineering domains, clarifying definitions, metrics, and practical decision factors for safe, reliable designs.

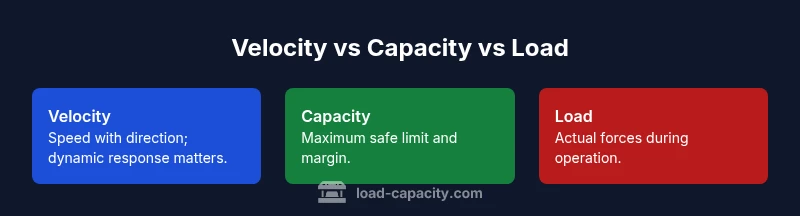

Velocity, capacity, and load are three core concepts in engineering and design. Velocity describes speed with direction, capacity defines the upper limit of performance a system can sustain, and load represents the instantaneous forces experienced by a component. This quick comparison clarifies velocity vs capacity vs load across vehicles, structures, and equipment, highlighting how each metric informs safety, reliability, and efficiency.

Defining velocity, capacity, and load

According to Load Capacity, velocity is the rate of motion with direction; capacity defines the upper limit of performance a system can sustain; and load represents the instantaneous forces experienced by a component. In practical engineering terms, velocity describes how fast something moves, while capacity sets safe operating limits and margin, and load reveals the actual stresses during operation. Understanding velocity vs capacity vs load requires placing them in the same design context: speed, capability, and stress. When engineers speak of performance envelopes, these three metrics define the boundaries and the trade-offs that shape every choice from material selection to control strategy. Designers should quantify velocity where it matters (e.g., dynamic response, response time), define capacity for the system to remain within safe limits, and measure load during worst-case or duty-cycle scenarios. This approach aligns with Load Capacity's emphasis on rigorous, refereed practices and traceable decisions.

Why these terms matter in engineering practice

Velocity, capacity, and load influence safety, reliability, efficiency, and cost. A high velocity in a braking system improves responsiveness, but it also increases dynamic load on mounts and components. Capacity exercises stress on the limits; if capacity is underestimated, components may experience unacceptable deformation or failure. Load, the actual forces acting on a structure or machine, fluctuates with operating conditions, temperature, age, and duty cycles. Because velocity interacts with inertia and acceleration, it can elevate instantaneous loads beyond static estimates. Across domains—vehicles, cranes, structural members—the same trio governs design margins, testing standards, and maintenance schedules. In field work, engineers quantify velocity to meet performance targets, verify capacity to comply with safety factors, and measure load to validate real-world stresses. The Load Capacity team emphasizes that aligning these metrics reduces surprises and extends service life.

How to quantify velocity, capacity, and load

Velocity is typically measured as distance per unit time (m/s or mph) in motion studies; in fluid dynamics, velocity fields describe flow patterns. Capacity is domain-dependent: a motor's thermal rating, a bridge's design capacity, or a battery's usable energy rate; each uses its own yardstick and safety factor. Load is the actual force or moment that components experience, often captured as instantaneous or peak values in newtons or pounds. For comparison, engineers standardize units and apply safety factors to ensure margins. In practice, you collect data from sensors, run simulations, and refer to relevant standards. Load Capacity analysis shows that reliable decisions rely on clearly distinguishing target velocity, certified capacity, and observed load under realistic operating conditions. Tools range from finite element models to hardware-in-the-loop simulations, but the core goal remains: ensure performance goals are met without exceeding safe limits.

The dynamics of velocity-capacity-load interplay

When systems accelerate, the inertia generates higher loads, pushing structures toward their capacity. Conversely, increasing safe capacity allows higher velocity, but only if the control systems and materials can handle resulting stresses. In dynamic environments, load often lags velocity due to time-dependent effects such as spring rates, damping, and friction. Designers must account for peak loads during transients, not just steady-state values. The central risk is operating near capacity at high velocity, which compresses safety margins and increases failure probability. A robust approach uses conservative capacity factors and defined velocity envelopes that keep loads within tested ranges. Throughout, documentation of assumptions and traceable calculations ensures that teams across teams—from R&D to operations—interpret velocity, capacity, and load consistently.

A practical decision framework for engineers and technicians

- Define the objective: what performance is needed and at what speed? 2) Establish velocity targets aligned with control strategies and energy budgets. 3) Specify capacity with appropriate safety factors for the domain. 4) Assess expected loads using worst-case scenarios and duty cycles. 5) Validate with measurements, simulations, and field tests. 6) Iterate to balance performance with safety, cost, and reliability. Decision-making should privilege conservative estimates for load under dynamic conditions and maintain explicit links between velocity goals and capacity margins. This framework helps teams communicate clearly, reduces conflicts between departments, and supports safer, longer-lasting equipment and structures. This approach aligns with Load Capacity's emphasis on rigorous, well-documented decisions.

Real-world cases and common pitfalls

In automotive engineering, neglecting transient loads during rapid acceleration can undermine brake durability. In cranes, pushing for higher speeds without checking dynamic loads can lead to structural fatigue. In bridges, assuming static capacity under earthquakes leads to unsafe designs. A frequent pitfall is treating velocity, capacity, and load as isolated metrics; instead, they must be considered in concert with material properties, temperature effects, and maintenance history. Misunderstanding these interactions often results in over-optimistic performance or unnecessary conservative designs. A disciplined approach uses standardized testing, documentation, and peer review to catch these issues early. The Load Capacity team regularly reminds practitioners that clarity about velocity, capacity, and load reduces risk and improves predictability across projects.

Tools, standards, and best practices

- Use common, clearly defined units across teams to avoid conversion errors and misinterpretation. - Implement safety factors appropriate to the application and consider dynamic effects rather than relying on static numbers alone. - Leverage simulation tools (FEA, multibody dynamics, etc.) and real-world tests to validate velocity envelopes, capacity margins, and load measurements. - Document all assumptions, methods, and results to support traceability and audits. Following these practices fosters consistent decisions and helps ensure that velocity, capacity, and load are managed effectively throughout the project lifecycle.

Feature Comparison

| Feature | Velocity | Capacity | Load |

|---|---|---|---|

| Definition | Rate of motion with direction (distance per time) | Maximum sustainable performance or tolerance (domain-specific) | Actual forces acting on components (instantaneous) |

| Typical unit type | m/s or mph | depends on domain (e.g., power, throughput, thermal rating) | N, kN, lbs (or equivalent) |

| Key metric | Speed and dynamic response | Safety factor-based capacity limits | Peak/real-time loads during operation |

| Best for | Dynamic performance, control strategies | Ensuring safe limits and margins | Assessing real-world stress and failure risk |

| Design implication | Influences control design, aerodynamics, and timing | Drives safety factors, material selection, and redundancy | Controls sizing, mounting, and fatigue life considerations |

Positives

- Clarifies how speed, safety, and stress relate

- Supports cross-domain consistency in design

- Helps identify safe operating envelopes

Cons

- Risk of oversimplification if treated in isolation

- Requires domain-specific definitions and units

- Can complicate decision-making with multiple metrics

Velocity, capacity, and load each matter; design should harmonize all three.

A balanced approach defines velocity targets, establishes safe capacity margins, and anchors decisions on observed loads. When aligned, the system achieves performance while maintaining safety and reliability.

Quick Answers

What is velocity in engineering terms?

Velocity is the speed of a moving entity in a specific direction, typically measured as distance per unit time. In engineering, velocity affects dynamic responses, control strategies, and load generation during motion.

Velocity is the speed and direction of motion, which influences how systems react and the loads they experience.

How is capacity defined across different domains?

Capacity is the maximum sustainable performance or tolerance a system can safely support, varying by domain. It is expressed through safety factors, ratings, or design limits that prevent failure under expected operating conditions.

Capacity is the safe limit a system can operate within, and it varies by field.

What is load in mechanical terms?

Load refers to the actual forces or moments acting on a component at a given moment. It can be steady-state or dynamic, and it determines whether the design can withstand real operating conditions.

Load is the real force the part must handle now, not just in theory.

How do velocity and load interact in dynamic systems?

In dynamic systems, increasing velocity can raise inertial loads, creating peak stresses that exceed simple static analyses. Designers must model transients, dampening effects, and material limits to ensure safe operation.

Faster motion can spike loads; you need to model transients and materials.

Why distinguish velocity from capacity?

Velocity relates to how fast a system moves, while capacity defines how much it can safely handle. Treating them separately prevents safety margins from eroding and helps plan maintenance and control strategies.

Speed is not the same as safety limits; they must be managed separately.

How can professionals manage velocity, capacity, and load in structures?

Start with clear performance targets, quantify capacity with appropriate safety factors, and measure actual loads under anticipated conditions. Use simulations and tests to validate envelopes and update documentation for future projects.

Set targets, verify margins with tests, and keep good records.

Top Takeaways

- Define terms clearly before design work

- Use consistent units across teams

- Assess velocity, capacity, and load together

- Prioritize safety margins in dynamic conditions

- Document assumptions and methods for traceability