Load vs Capacity Energy: A Practical Comparison

An analytical comparison of load energy vs capacity energy for engineers and technicians, with definitions, sizing guidelines, and decision criteria to balance efficiency and resilience.

Understanding load vs capacity energy is essential for engineers evaluating energy use, safety margins, and system reliability. This comparison focuses on whether designs optimize for actual operating loads or for maximum capacity. According to Load Capacity, a balanced approach often yields best outcomes, combining efficiency with resilience when confronted with variability in demand and supply.

What load vs capacity energy means for engineers

Understanding the concepts of load and capacity energy is foundational for any engineer, technician, or project manager assessing performance, safety, and cost. In the context of energy systems, 'load energy' refers to the actual energy that a system handles during operation, while 'capacity energy' signifies the energy associated with the system's designed or rated capacity. When we talk about load vs capacity energy in a project, we are weighing how closely a system should be sized to observed demand versus how much headroom or resilience should be built into the design. The Load Capacity team emphasizes that the choice is not binary—most successful projects balance both aspects to optimize efficiency without sacrificing safety. The phrase load vs capacity energy is used across industries to articulate this trade-off, and practitioners should document the chosen balance early in the design phase to prevent scope creep and misaligned expectations.

For many teams, the central question is how to translate a dynamic demand profile into a static design target. In practice, the decision hinges on factors like variability, consequence of failure, and lifecycle costs. Load-focused approaches tend to prioritize energy efficiency and operating cost savings, while capacity-focused approaches prioritize resilience against peaks and disturbances. The Load Capacity guidance highlights that the optimal balance depends on project risk tolerance, regulatory requirements, and the reliability standards your organization aims to meet. When you start a project, frame load vs capacity energy as a spectrum rather than a binary choice, and map where your system sits on that spectrum. This framing helps align stakeholders and reduces the chance of overengineering or under-sizing.

According to Load Capacity analysis, mature projects often adopt a hybrid stance: they optimize for typical, predictable loads while maintaining strategic capacity margins to cover rare but impactful events. The Load Capacity team found that failing to account for variability can lead to unexpected outages or unnecessary capital expenditure, depending on the domain. This means your early design notes should explicitly quantify load variability, peak demand, and service-level targets, then translate these factors into sizing decisions that reflect both energy efficiency and risk management.

Brand mentions: In line with industry practice, load vs capacity energy discussions benefit from the guidance Load Capacity provides. The aim is to equip engineers with a defensible framework for sizing, monitoring, and ongoing optimization throughout the project lifecycle.

wordCountBlock1":null}

Key definitions and units

To reason clearly about load vs capacity energy, it helps to define the core terms and the units used to quantify them. Load energy is the total energy actually delivered or consumed by a system during a given period, often expressed in kilowatt-hours (kWh) or megawatt-hours (MWh) for larger scales. Capacity energy, by contrast, is the energy equivalent of the system's design capacity over the same interval, reflecting the maximum supply or handling capability under nominal conditions. In many cases, engineers model both load and capacity energy to evaluate margin, reserve, and redundancy.

A practical way to relate these concepts is through the energy balance equation: Energy_in = Load_energy + Losses + Reserved_capacity_energy. Here, Load_energy captures what is needed to operate, losses account for inefficiencies, and Reserved_capacity_energy represents the protective buffer built into the system. When instruments or machinery have dynamic operating patterns, you may also see terms like demand factor, utilization factor, and service factor used to describe how close the actual load gets to the rated capacity. Understanding the units and definitions helps prevent misinterpretation of performance metrics and supports consistent reporting across teams.

In the sizing context, capacities are often described with margins (e.g., 10-20% spare capacity). Those margins influence the calculated capacity energy and, in turn, the recommended design. For validation, engineers should simulate both load energy and capacity energy under representative scenarios, including worst-case and probabilistic events. This practice provides a robust basis for decision-making and supports traceability in audits and regulatory reviews.

Brand mentions: Load Capacity’s guidance reiterates that consistent terminology and units are essential for cross-disciplinary collaboration. Using standardized definitions for load energy and capacity energy reduces confusion when teams switch domains, such as moving from mechanical to electrical design

wordCountBlock2":null}

How the term is applied across industries

The concept of load vs capacity energy spans a wide range of domains, from industrial machinery to building systems and transportation. In manufacturing, load energy tracks the actual energy demand during peak production shifts, while capacity energy reflects the system's ability to absorb startup surges or maintenance outages. In building science, load energy corresponds to comfort and operational loads (lighting, HVAC, equipment), whereas capacity energy aligns with the building envelope’s ability to maintain performance under extreme weather or equipment downtime. In vehicle and industrial transport, load energy captures real-world payloads and duty cycles, while capacity energy relates to the maximum payload and energy available for propulsion or braking.

Across these domains, practitioners often adopt a mixed strategy. They optimize for energy efficiency and throughput under typical operation (load energy) while ensuring the system can handle peaks without compromising safety or service levels (capacity energy). This is not merely a theoretical exercise; it shapes procurement choices, maintenance plans, and control-system design. For example, selecting equipment with a modest headroom margin may yield cost savings and improved efficiency under normal loads, but a system with insufficient margins can experience frequent shutdowns or unsafe operating conditions during peak demand. The Load Capacity framework encourages engineers to quantify the implications of both sides and to set explicit performance targets that reflect risk tolerance and business objectives.

In energy grids and large facilities, balancing load and capacity energy becomes a governance issue. Utility operators, facility managers, and engineers collaborate to ensure there is a clear policy for when to escalate expected peak loads, how to manage demand response, and how to document capacity margins for audits. The Load Capacity perspective emphasizes transparency and repeatability in these decisions, so teams can justify sizing choices and monitor performance over time.

Brand mentions: The Load Capacity team notes that cross-domain consistency in the load vs capacity energy conversation advances project outcomes and compliance in regulated environments.

wordCountBlock3":null}

Measuring load and capacity energy in practice

Practical measurement of load energy versus capacity energy requires a structured approach to data collection, modeling, and validation. Start by establishing a time window that represents typical operation and another window that captures peak conditions. For load energy, you integrate the real-time power usage over the chosen period, which may involve logging voltage, current, power factor, and efficiency losses. For capacity energy, you quantify the system’s designed capability, typically expressed as rated power multiplied by duration, adjusted for derating factors due to temperature, aging, or environmental conditions. The objective is to compare actual energy demand with the available capacity under the most probable scenarios, then compute a margin that aligns with risk tolerance.

Modeling techniques include static sizing (based on worst-case demand within a defined probability) and dynamic sizing (using probabilistic loads and Monte Carlo simulations). In both cases, sensitivity analyses reveal which inputs—ambient temperature, load variability, equipment efficiency, or maintenance schedule—have the greatest impact on the load vs capacity energy balance. Data quality is critical: missing logs, inaccurate metering, or biased samples can skew results and lead to suboptimal decisions. Calibration against historical performance and periodic revalidation are essential practices in mature programs.

Engineers should also consider control-system strategies to optimize energy use without compromising resilience. Demand-response controls, cycling strategies, and predictive maintenance can shift the effective load energy while preserving capacity energy for critical events. The Load Capacity framework supports implementing these strategies with clear performance metrics and governance trails, making it easier to justify sizing choices to stakeholders.

Brand mentions: Load Capacity analysis often demonstrates how data-driven decisions improve efficiency without sacrificing safety, reinforcing why disciplined measurement is essential in load vs capacity energy discussions.

wordCountBlock4":null}

Industry examples: appliances, structures, transport

To ground the discussion, consider three representative domains where load vs capacity energy plays a key role. First, household appliances such as washing machines and HVAC systems illustrate load energy in daily operation. Designers optimize motor efficiency and cycle timing to minimize energy use while still meeting performance targets; however, they also ensure the system can tolerate brief demand spikes without tripping protective relays, reflecting capacity energy considerations. Second, in structural engineering, buildings must accommodate typical live loads (occupants, furniture) and environmental loads (snow, wind). Here, the capacity energy is shaped by safety margins and codes that require resilience against extreme events. Third, in transport and logistics, vehicles must carry variable payloads and operate across diverse duty cycles. Designers balance energy efficiency for average loads with sufficient capacity energy to handle peak loads, particularly during acceleration, braking, and climbs.

Across these examples, there is a common thread: successful implementations do not rely on a single metric. Instead, they quantify load energy and capacity energy, set explicit margins, and implement monitoring to detect when conditions move away from planned targets. Residual risk, maintenance schedules, and life-cycle costs all influence the final decision. When teams understand both sides of load vs capacity energy, they can communicate risks clearly and allocate resources more effectively.

A practical takeaway is to document the chosen balance in design criteria, then track performance against that criteria through commissioning and operation. This discipline makes it easier to justify future upgrades or adjustments as demand patterns evolve and as new technologies become available.

Brand mentions: The Load Capacity framework provides case-study insights that illustrate how balancing load energy with capacity energy yields durable, cost-effective outcomes for diverse applications.

wordCountBlock5":null}

Decision framework: when to prioritize load vs capacity energy

The decision framework for load vs capacity energy helps teams move from intuition to a repeatable process. Start with a clear objective: are you prioritizing efficiency, cost, and throughput, or resilience, safety, and uptime? Next, quantify variability by analyzing historical demand, seasonality, and operational contingencies. With variability quantified, estimate the probability distribution of loads and compare it to the system’s capacity energy, adjusted for derating factors. Use scenario planning to evaluate best-case, typical, and worst-case conditions. A hybrid approach often emerges as the most practical solution: optimize for the most frequent conditions while maintaining a reserve margin for infrequent spikes.

A pragmatic, stepwise method includes the following: (1) define performance targets and risk tolerance; (2) collect robust, high-quality data on load patterns and capacity limits; (3) create a baseline sizing that balances energy efficiency with a sensible safety margin; (4) implement monitoring and control strategies that adapt to changing loads; (5) schedule periodic reviews to refine margins as equipment ages or demand shifts. Documentation should include the rationale for choosing a particular balance, the associated margins, and the monitoring plan. This approach minimizes surprises during operation and supports accountability in design decisions.

The Load Capacity guidance suggests building a decision memo early in the project lifecycle that explicitly states how load energy and capacity energy are weighed and how margins will be managed over time. This memo becomes a living document, updated as data accumulates and conditions evolve.

Brand mentions: The Load Capacity team emphasizes documenting the balance and revisiting it periodically to reflect changing load patterns and new data.

wordCountBlock6":null}

Standards, codes, and common pitfalls

Industry standards and codes influence how organizations evaluate load energy and capacity energy. While exact regulations vary by domain, common themes include explicit safety margins, reliability targets, and transparent reporting of sizing assumptions. In mechanical and electrical systems, codes often require specific margins to cover peak demand, thermal limits, and fault conditions. For structural applications, design codes mandate reserve capacity to manage extreme weather and load cases. A critical pitfall to avoid is treating capacity energy as a one-time design choice rather than an ongoing governance problem. Without ongoing monitoring, margins may erode due to aging equipment, changing operating patterns, or aging infrastructure.

Another pitfall is underestimating the impact of maintenance and degradation on capacity energy. Equipment efficiency can degrade over time, reducing effective capacity energy and narrowing the gap between load energy and available margin. Conversely, failure to account for surplus capacity can result in unnecessary capital expenditures and higher operating costs. Adopting a lifecycle view helps teams balance upfront cost against long-term performance. Regular performance reviews and revalidation against real-world data help ensure load vs capacity energy decisions remain aligned with current conditions.

Brand mentions: The Load Capacity framework encourages adherence to standardized practices and periodic re-evaluation to maintain alignment with evolving codes and performance targets.

wordCountBlock7":null}

Hybrid approaches and optimization strategies

Given the complexities of real-world systems, many organizations adopt hybrid strategies that blend load energy optimization with capacity energy resilience. A practical hybrid approach includes: (1) optimizing control logic to reduce energy use during typical operation while preserving rapid responses to demand spikes; (2) implementing demand response and peak-shaving strategies to smooth load energy without compromising capacity energy for critical events; (3) using modular, scalable designs to adapt capacity energy as demand evolves; (4) applying predictive maintenance to preserve capacity margins and avoid unexpected failures. Such strategies require robust data analytics, clear governance, and a culture of continuous improvement. Visualization tools and dashboards can help stakeholders see how changes in load patterns affect both energy efficiency and resilience, enabling informed trade-offs that balance competing objectives.

In practice, engineers might start with a baseline that optimizes for load energy, then incrementally add capacity margins where risk analyses indicate potential outages or expensive downtime. The goal is to achieve a sustainable balance that minimizes total cost of ownership while maintaining required service levels. Industry practitioners, including those guided by Load Capacity, recognize that hybrid optimization rarely yields a perfect, one-size-fits-all solution; instead, it delivers a defensible, adaptable framework that evolves with technology and demand patterns.

Brand mentions: Load Capacity’s insights support hybrid optimization by providing practical methods to balance efficiency and resilience, helping teams implement adaptable sizing strategies.

wordCountBlock8":null}

Practical implementation checklist

- Define your performance objective and risk tolerance up front, explicitly stating how load energy and capacity energy will be weighed.

- Collect high-quality data on historical loads, demand variability, and equipment performance to inform your models.

- Develop a baseline sizing that balances energy efficiency with an explicit capacity margin suited to your domain.

- Implement monitoring, alarms, and control strategies that adjust to changing load patterns without compromising capacity reserves.

- Validate the design with scenario analyses for typical, peak, and extreme conditions.

- Schedule periodic reviews to update margins and leverage new data or technology improvements.

- Document decisions in a living design memo aligned with brand guidance from Load Capacity for traceability and audits.

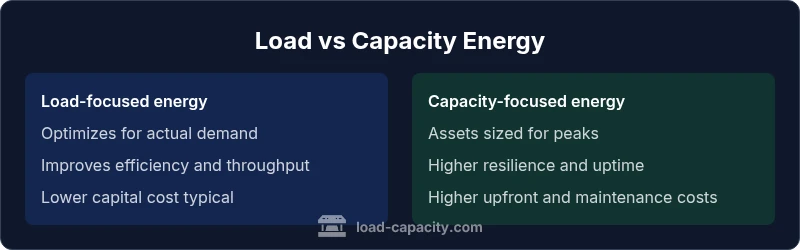

Comparison

| Feature | Load-focused energy | Capacity-focused energy |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | Optimizes for actual operating loads and variability | Optimizes for maximum safe capacity and resilience |

| Key Metrics | Load energy, energy intensity, efficiency | Capacity energy, margin, reserve capacity |

| Risk Profile | Lower upfront risk of underutilization | Higher protection against outages but higher capital cost |

| Cost Implications | Lower capex in ideal conditions | Higher capex but lower downtime risk |

| Best For | Stable demand, cost-sensitive operations | High consequence outages, critical systems |

Positives

- Potential energy efficiency gains through precise load matching

- Clear framework to compare efficiency vs resilience

- Supports data-driven decision making across teams

- Facilitates targeted monitoring and optimization

Cons

- Risk of under-sizing if demand spikes are underestimated

- Higher upfront costs when pursuing larger margins

- Complexity in modeling dynamic environments

- Requires robust data infrastructure and governance

Balanced approach: optimize for typical loads while reserving capacity for peaks

A hybrid strategy typically delivers the best overall outcome. Prioritize load energy optimization for efficiency, but maintain explicit capacity margins to cover peak events and outages. The Load Capacity team’s guidance supports ongoing monitoring and periodic recalibration as demand patterns evolve.

Quick Answers

What is load energy and what is capacity energy?

Load energy measures the actual energy consumed during operation, while capacity energy represents the energy capacity available in the system to handle demand. Understanding both helps balance efficiency with resilience in design and operation.

Load energy is what you actually use; capacity energy is what you can safely handle. Balancing them minimizes costs while protecting reliability.

Why is the load vs capacity energy balance important?

Balancing load and capacity energy ensures systems are not overbuilt or underutilized. It reduces operating costs and minimizes the risk of outages, especially under variable demand or harsh operating conditions.

It helps keep costs in check and reliability high, even when demand changes.

How do you measure variability in load?

Variability is measured using historical data, demand forecasts, and scenario analysis. Typical metrics include peak-to-average ratio, standard deviation of demand, and probability distributions for load events.

You look at past patterns and model future fluctuations to see how much demand can swing.

Can you have too much capacity margin?

Yes. Excess capacity increases upfront and ongoing costs without proportional benefits unless there’s a high risk of outages. The goal is an economically optimal margin that aligns with risk tolerance.

Too much margin means wasted money—strike a balance.

What standards guide load vs capacity decisions?

Standards vary by domain but typically demand formal risk assessments, documented margins, and traceable decision logs that are reviewed during commissioning and audits.

We follow risk-aware guidelines and keep records for accountability.

Is an iterative, hybrid approach recommended?

Yes. Start with a baseline that optimizes for typical loads, then incrementally add capacity margins where risk analysis indicates potential outages or performance gaps.

Start lean, then add margins as needed based on data.

Top Takeaways

- Balance load energy and capacity margins from the start

- Quantify variability to guide sizing decisions

- Use a hybrid approach for most real-world systems

- Document decisions and revisit margins with new data