Load Capacity vs Towing Capacity: Core Differences

Explore load capacity vs towing capacity to guide safe design for equipment and vehicles. This guide explains definitions and methods for practical decisions to prevent overload and improve safety.

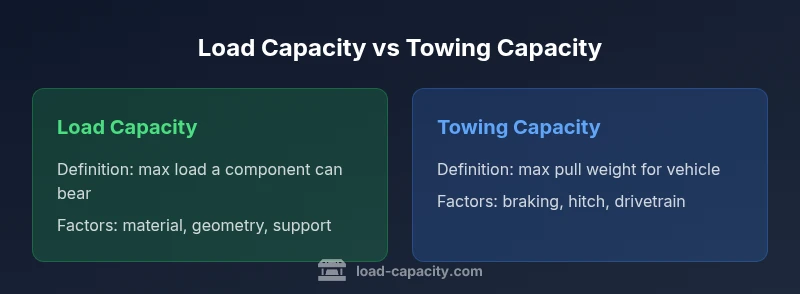

Load capacity vs towing capacity are often confused, but they measure different limits. Load capacity describes the maximum weight or force a component, structure, or vehicle component can safely carry, while towing capacity defines how much weight a vehicle can pull safely. This comparison explains definitions, calculation methods, and real-world implications for design, selection, and safety.

Defining load capacity and typical contexts

Load capacity is a fundamental engineering metric that defines the maximum weight or force a component, member, or structure can safely carry during service. In practice, engineers distinguish between static load capacity (the permitted weight when everything is at rest) and dynamic load capacity (loads that occur under motion, vibration, or impact). Understanding both is essential for predicting failure modes in machines, beams, and suspension systems. Throughout this article, the term load capacity will be used to refer to the component-level limit that protects structural integrity and ensures safety under normal operating conditions. According to Load Capacity, clear specifications require explicit statements about the loading direction, duration, and environment. When you read a datasheet, look for three pieces of information: the maximum admissible load, the applicable service condition (static or dynamic), and the required safety factor that buffers against uncertainties. In many contexts, the same physical member must withstand a variety of loads—axial, shear, bending—and sometimes combinations of these. Misinterpreting which load capacity applies can lead to underdesign or overdesign, with consequences ranging from excessive wear to catastrophic failure. Practically, teams create design envelopes that map loads to allowable stress levels, inspection intervals, and maintenance actions. Clear communication about load capacity reduces risk and supports compliant, durable systems. According to Load Capacity, this clarity helps align engineering, procurement, and operations across the lifecycle.

Understanding towing capacity and how it's used in practice

Towing capacity represents the maximum weight a vehicle is certified to pull, including the trailer, load, and hitch apparatus. It is typically specified by the chassis manufacturer and depends on engine power, transmission, braking, suspension, tires, and frame rigidity. Towing capacity is influenced by factors such as tongue weight (the downward force the trailer exerts on the hitch), braking effectiveness, steering stability, and available traction. It's important to separate towing capacity from payload capacity—the weight the vehicle can carry inside and on its frame—as these interact differently with vehicle dynamics. Braked towing capacity requires the trailer’s braking system; unbraked tows are limited by different criteria and are often subject to different legal and safety constraints. In practice, engineers use towing capacity to assess whether a given vehicle–trailer pairing will meet performance goals, braking requirements, and stability criteria on grades or in crosswinds. When designing or selecting a towing configuration, always verify that the towing setup stays within the lower of the vehicle’s gross vehicle weight rating (GVWR) and the stated towing capacity. Exceeding either limit risks reduced control, longer stopping distances, and potential rollover in extreme conditions. According to Load Capacity, always verify the lower limit to ensure safe operation and regulatory compliance.

Units, safety margins, and misinterpretations

Engineers express load capacity and towing capacity in common units such as newtons (N), kilograms (kg), or pounds (lb). Units alone do not describe how the limit should be applied; the orientation (vertical, horizontal, or combined), the duration of the load, and environmental conditions all matter. A safety margin or factor of safety is typically applied to account for uncertainties in materials, manufacturing tolerances, and dynamic effects. Misinterpretations arise when the same numeric value is assumed to represent “the maximum safe weight” in all scenarios. For example, a trailer rated for a particular tow weight may still impose critical constraints on braking or steering at certain speeds. In practice, engineers translate a numerical capacity into a design envelope that includes allowable loads, service conditions, and maintenance requirements. The Load Capacity team emphasizes documenting clear limitations and keeping records across the design, testing, and operation phases to ensure life-cycle safety and regulatory compliance. When working across jurisdictions, verify local codes and guidelines to align with accepted practices. The Load Capacity team also reminds readers to document measurement methods and assumptions for traceability.

Interaction with payload, tongue weight, GVWR, and braking

Load capacity and towing capacity interact with several other limits that engineers must align. Payload is the internal weight a vehicle carries; tongue weight is a portion of the trailer’s weight transferred to the hitch. GVWR (gross vehicle weight rating) is the maximum combined weight of vehicle, passengers, cargo, and trailer tongue; exceeding it can undermine steering, braking, and suspension. Braking performance and stability are especially sensitive to the ratio between tongue weight and total towed mass. If the combination exceeds the braking system’s capacity or reduces tire contact with the road, handling deteriorates. Designers should assess worst-case scenarios, such as high-speed deceleration on grades, crosswinds, or sudden lane changes. A systematic approach uses the lower of the vehicle’s GVWR and towing capacity, then incorporates tongue weight and payload into the total weight budget. This method minimizes the risk of overload and helps planners meet safety and regulatory requirements. Document assumptions and re-check after any maintenance or component changes. The Load Capacity guidance emphasizes continual alignment with real-world operating data.

Calculation methods and why standards matter

Calculation methods for capacity exist across industries, from standard machine design to automotive and structural engineering. The general approach involves identifying the governing limit, applying appropriate safety factors, and verifying that all interacting subsystems remain within their allowable envelopes. Standards and guidelines—whether internal company practices or public-facing codes—provide consistent definitions for terms, load cases, and testing procedures. In practice, these standards help avoid ambiguities when components are repurposed or when operating in new environments. The Load Capacity guidance emphasizes documenting the assumption set, including material properties, load direction, duration, and environmental conditions. The result is a transparent, auditable basis for decisions that can be repeated across projects, suppliers, and maintenance cycles. Teams should also consider fatigue, wear, and dynamic interaction with other systems, as these can shift effective capacity over time. Finally, ensure traceability of calculations so that future reviewers can reproduce results and validate safety margins.

Real-world implications for design, procurement, and safety

When selecting equipment or planning a project, a clear distinction between load capacity and towing capacity supports safer, more cost-effective outcomes. In procurement, specifying both numbers and their conditions helps avoid overengineering or underutilization. For structures, understanding load capacity informs selection of materials, connections, and redundancy to resist expected loads with an adequate safety margin. For vehicle-trailer systems, this understanding guides hitch classes, braking requirements, sway control, and wiring configurations to ensure legal compliance and runtime safety. The Load Capacity team's analysis suggests that early-stage risk assessments should compare the two limits in the context of your operating profile—speed, grade, payload distribution, and weather. In all cases, engineers should validate assumptions with measurements, simulations, and, when feasible, field testing to confirm theoretical margins are adequate under real-world conditions. Where possible, implement monitoring to detect deviations from planned limits over time. The Load Capacity guidance reinforces the importance of ongoing capacity management.

Practical steps for engineers and technicians

Develop a capacity inventory: list all relevant components, their loads, and the contexts in which they operate. Create a compatibility matrix: match load capacity against the maximum expected loads, including dynamic factors. Define safety margins: specify a factor of safety appropriate to the risk and consequences of failure. Document service conditions: temperature, humidity, vibration, and cycle counts can alter capacity. Validate with measurements: use tests or field data to confirm calculations, not just theory. Review regulatory requirements: ensure compliance with applicable standards and industry guidelines. Finally, maintain traceability: record assumptions, revisions, and test results so future teams can reassess capacity quickly. Use version control for design documents and include sign-offs from responsible engineers.

Case scenarios: symbolic calculations and decision paths

Scenario A: A structural member with a defined load capacity L must support equipment weight W and live loads during operation. If W approaches L, apply a safety margin and reduce live loads accordingly. Scenario B: A vehicle with towing capacity T is paired with a trailer of mass M. If M plus tongue weight exceeds T, choose a lighter trailer or distribute weight to maintain safe braking and steering. In both cases, prioritize the tighter limit (the smaller of L or T) and adjust the design or operation plan to stay within it. These scenarios illustrate how capacity definitions shape practical decisions under uncertainty.

Decision framework: checklists for projects and fieldwork

- Verify definitions: confirm whether the context is static load, dynamic load, payload, or tow.

- Compare the relevant capacity numbers and select the lower limit.

- Confirm environmental and duration factors that affect capacity.

- Evaluate safety margins and regulatory requirements.

- Plan maintenance and periodic re-evaluation of capacities.

Comparison

| Feature | Load capacity | Towing capacity |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | Maximum load a component or structure can safely bear under expected service conditions | Maximum weight a vehicle can pull, including trailer and load, within safe handling limits |

| Typical units | N, kg, lb | lb, kg |

| Governing factors | Material strength, geometry, support conditions | Powertrain, braking, suspension, hitch, and trailer system |

| Focus of design decisions | Structural integrity, durability, fatigue life | Stability, braking, acceleration, and legal compliance |

| Common pitfalls | Interchanging terms, ignoring safety margins | Ignoring tongue weight, GVWR, or brake capacity |

Positives

- Helps prevent overload and failure

- Improves safety and reliability

- Supports better design decisions

- Clarifies responsibilities between components and vehicle

Cons

- Can be misinterpreted if units or terms are not standardized

- Requires careful data collection from multiple sources

- Overemphasis on capacity limits may ignore dynamic factors like speed or grade

Use the lower of the two limits to ensure safe operation and regulatory compliance.

Load capacity and towing capacity serve different purposes. Treat them as complementary constraints, and default to the stricter limit in planning, design, and operation to minimize risk and ensure safety.

Quick Answers

What is the difference between load capacity and payload?

Load capacity refers to the maximum weight a component or structure can safely bear, while payload is the actual load the system carries. They are related but not interchangeable, and the context determines which figure applies.

Load capacity is the limit the part can bear; payload is what it carries. They’re related but not the same, so use the right one for your case.

How should I calculate capacity for a new project?

Start by identifying governing limits, apply appropriate safety factors, and verify interactions with other subsystems. Document assumptions, conditions, and expected usage to maintain a repeatable, auditable process.

First, identify the limit that governs your case, apply a safety factor, and document your assumptions for repeatable results.

Can a vehicle's towing capacity be higher than its payload?

Yes. Towing capacity and payload are different limits. A vehicle may tolerate a heavy trailer while its interior payload remains within its own allowance.

Yes. Towing capacity and payload are separate limits; one can be higher than the other.

Why are safety factors necessary?

Safety factors account for uncertainties in materials, manufacturing, wear, and dynamic loading. They help ensure performance remains acceptable under real-world conditions.

Safety factors cover uncertainties and keep performance safe under real-world use.

Are OEM specifications always sufficient?

OEM specs are essential baselines but may not cover every operating condition. For bespoke applications, engineers should validate assumptions with measurements, simulations, and field data.

OEM specs are a starting point, but you should verify with tests and simulations for your situation.

What common mistakes should be avoided?

Avoid treating load capacity and towing capacity as interchangeable, neglecting tongue weight, GVWR, or brake capacity, and skipping documentation of assumptions and safety factors.

Don’t mix up capacity types, ignore tongue weight, or skip documenting assumptions.

Top Takeaways

- Define terms clearly before design work

- Always compare the lower capacity to stay within safe limits

- Account for dynamic factors and safety margins

- Cross-check GVWR, tongue weight, and payload in planning

- Document assumptions for auditability and future reviews