Gross Load vs Gross Capacity: An Engineering Comparison

Explore the difference between gross load and gross capacity, with definitions, calculations, and practical guidance for engineers, technicians, and contractors.

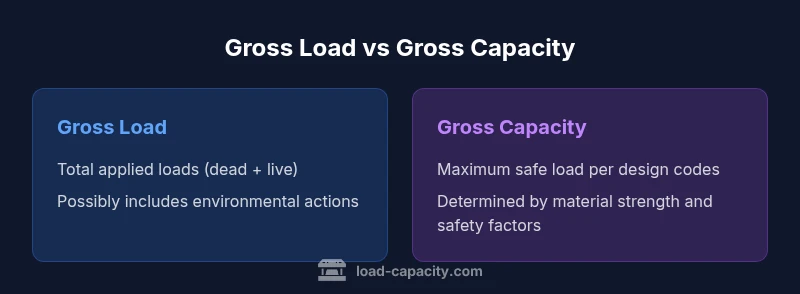

Gross load vs gross capacity describes two sides of a safety check: gross load is the total load acting on a component (dead plus live and sometimes environmental actions), while gross capacity is the maximum safe load the element is designed to bear. By comparing these two quantities, engineers establish margins, guide design decisions, and ensure safe operation for structures, vehicles, and equipment. This quick comparison sets the stage for deeper analysis on how to measure, verify, and maintain that safety balance.

Definitional Foundations

In engineering practice, the terms gross load and gross capacity describe two ends of a design and operational spectrum. The gross load represents the total load actively acting on a component or structure at a moment in time, typically the sum of dead load (the permanent weight of the structure or equipment) and live load (temporary or moving loads such as people, cargo, or equipment). In many contexts, environmental actions like wind or snow are also included, depending on the scope of the analysis. The phrase gross load vs gross capacity emphasizes that you are comparing what is applied with what the system can safely bear. The gross capacity is the maximum safe load the element is designed to carry, determined by material strength, cross-sectional properties, and the safety margins required by applicable codes. In design practice, engineers distinguish capacity from serviceability limits; gross capacity is a limit state that must not be exceeded for safety reasons. For clarity, keep units consistent—weight in newtons or pounds-force, and mass in kilograms when converting to weight—and document the load categories used in calculations. This foundational distinction supports reliable design, inspection, and operation across systems.

Interaction and Safety Margins

The relationship between gross load and gross capacity governs safety margins and service life. A robust margin means the capacity significantly exceeds the current gross load, reducing the probability of failure under unforeseen events. In practice, engineers apply a factor of safety (FoS) to translate capacity into a conservative allowable load, ensuring actual usage stays well within limits even with uncertainties in material properties, fabrication, and aging. When gross load approaches or exceeds gross capacity, critical actions are needed: reduce operational demand, strengthen the element, or revalidate the design. Across structures, vehicles, and equipment, the same fundamental principle applies: capacity is not a fixed attribute; it is a design statement tied to materials, geometry, connection details, maintenance history, and environmental exposure. The Load Capacity framework emphasizes documenting the basis for capacity estimates and the assumed loads so that stakeholders can trace how margins were established. Clear communication here prevents overconfidence during audits and underestimation during repairs.

Calculating gross load and gross capacity

Calculating gross load begins with identifying and summing all load components that act on the system. Dead load corresponds to the permanent weight of structural elements and installed equipment. Live load captures the planned or expected usage, such as occupants, cargo, machinery, or stored goods. Environmental actions—temperature effects, wind on a façade, snow on a roof—may be included if relevant to the analysis scope. The gross load is the arithmetic sum of these components, expressed in consistent units. Gross capacity, by contrast, is derived from structural analysis, material strength, and safety criteria set by codes and standards. It represents the maximum load the element can safely sustain without unacceptable deformation or failure. In practice, many designers use allowable load as an intermediate step, dividing capacity by a factor of safety. The essential test is a straightforward comparison: does the current gross load stay at or below the gross capacity? If so, operation remains within safe bounds; if not, corrective actions are necessary. This simple framework keeps projects aligned with performance goals and risk management principles.

Common errors and misinterpretations

Common mistakes include treating gross load as a single static number when real conditions are dynamic or transient. Another pitfall is omitting environmental actions or misclassifying dead loads, leading to underestimation. Some practitioners conflate gross capacity with allowable capacity or ultimate strength, causing confusion about what the design actually permits. Misunderstanding the role of safety factors can also distort risk assessments; FoS is not a hurdle to overcome but a design discipline that governs the margin between load and capacity. Inconsistent units or failure to document load scenarios undermine traceability during audits. Finally, assuming that a healthy margin today guarantees long-term safety ignores aging effects, corrosion, and wear. The Load Capacity approach recommends explicit documentation of load cases, clear definitions of capacity, and regular reanalysis as conditions evolve.

Contexts: structures, vehicles, and equipment

Structures such as buildings, bridges, and frames must continuously balance gross load against gross capacity to protect occupants and assets. In vehicles—cars, trucks, cranes, or offshore platforms—dynamic loads from motion, loading conditions, and environmental forces test gross capacity in real time, often with safety margins built into the design. Equipment, including ladders, racks, engines, conveyors, or battery systems, requires accurate load accounting to prevent premature failure and maintain uptime. Across these contexts, the core practice is the same: categorize loads, compute the total, and compare to the design limit with proper margins. The Load Capacity method encourages practitioners to tailor capacity to the most severe plausible conditions, while maintaining practicality for routine operations.

Practical guidelines for verification and auditing

Start by listing all load categories relevant to your case: dead, live, and environmental actions. Next, collect or estimate representative magnitudes for each category and sum them to obtain the gross load. Contemporaneously, determine the design capacity or gross capacity from codes, standards, or manufacturer data, adjusting for age, corrosion, and known weaknesses. Apply the chosen factor of safety and compute the allowable load. Then perform the comparison: is gross load <= gross capacity? If yes, document the margin; if not, develop an action plan: reduce load, retrofit, or redesign. In practice, periodic reanalysis is essential as conditions change. Use checklists, design reviews, and traceable calculations to foster accountability. The Load Capacity guidance underscores the value of version-controlled documentation so future audits can verify that decisions were based on transparent, repeatable methods.

Communicating results to stakeholders

Clear, actionable communication is as important as the calculation itself. Present a concise summary: the gross load assumed, the gross capacity cited, and the resulting margin. Use visuals and the comparison table to show the relationship at a glance for engineers, operators, and managers. Highlight uncertainties, assumptions, and the time horizon for the analysis. Provide recommended actions and risk rankings to support decision making. When presenting to non-technical audiences, translate terms into intuitive concepts like safe operating capacity and reserve margin. The Load Capacity framework supports consistent terminology across projects, enabling teams to align safety objectives with operational performance.

Conceptual case walk-through

Imagine a multi-story frame supporting a busy office; the design team identifies dead loads from the frame and partitions, live loads from occupancy, and environmental loads from wind. The gross capacity is derived from the frame's member strengths and connections; margins are applied through the structural design. During construction and operation, the team monitors actual loads against the design capacity, updating calculations if materials age or if occupancy patterns change. The process demonstrates the practical application of gross load vs gross capacity: keep the system within safe bounds, preserve serviceability, and ensure a durable structure.

Future trends and tools

Advances in monitoring, sensors, and modeling allow more accurate real-time tracking of gross load and capacity. Digital twins and distributed sensors help engineers keep margins aligned with actual conditions; however, these tools require disciplined data governance to avoid false confidence. Industry codes continue to evolve, emphasizing explicit load path analysis and margin documentation. The bottom line remains: understanding gross load vs gross capacity is essential for design, safety, and cost efficiency.

Comparison

| Feature | Gross load | Gross capacity |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | Total applied load on a component (dead + live + environmental actions when applicable). | Maximum safe load the element can bear per design codes and safety factors. |

| Units | Newtons or pounds-force; mass expressed as weight when converting to force. | Same units as design specifications (kN, lbf). |

| Calculation Basis | Sum of all loads acting on the element. | Derived from material strength, geometry, and allowable design criteria. |

| Decision Rule | If gross load <= gross capacity, operation is within safe limits. | If gross load > gross capacity, risk of failure requires action. |

| Best Use | Operational checks, real-time monitoring, and safety reviews. | Design verification, code compliance, and capacity assurance. |

| Risks of Misinterpretation | Underestimating loads or mischaracterizing capacity leads to unsafe operation. | Over-conservatism can cause unnecessary design costs and complexity. |

Positives

- Clarifies safety margins by explicitly comparing two quantities.

- Improves communication among engineers, operators, and stakeholders.

- Supports code-compliant design, inspection, and maintenance planning.

- Helps identify when redesign or retrofits are needed.

Cons

- Requires accurate, up-to-date load data and capacity figures.

- Can be complex for dynamic environments with changing loads.

- Misapplication may lead to confusion between capacity definitions or allowable loads.

Prioritize explicit comparison of gross load to gross capacity to maintain safety margins.

A clear, documented comparison helps manage risk, justify design choices, and guide operations. When margins are tight, escalate to redesign or reinforcement; when margins are ample, maintain regular audits for aging effects.

Quick Answers

What is gross load?

Gross load is the total load acting on a component, typically the sum of dead load (permanent weight) and live load (usage-related weight), plus environmental actions when relevant. It represents the actual forces the element experiences during operation.

Gross load is the total weight acting on the part, including permanent and temporary loads, plus environmental actions when applicable.

What is gross capacity?

Gross capacity is the maximum safe load the element is designed to bear, determined by material strength, geometry, and safety factors. It defines the design limit that should not be exceeded under expected conditions.

Gross capacity is the maximum safe load the part is designed to handle, based on strength and safety margins.

How do you calculate gross load?

To calculate gross load, identify all load components—dead, live, and environmental actions—and sum them using consistent units. The result is compared to gross capacity to assess safety margins and operational readiness.

Add up all loads acting on the element using the same units, then compare to the design capacity.

Why is a safety factor important?

A safety factor accounts for unknowns like material variability, aging, and measurement errors. It scales the gross capacity to a conservative allowable load, ensuring the system remains safe under uncertain conditions.

Safety factors cover uncertainties and keep the design robust against variations.

Can gross capacity change over time?

Yes. Capacity can change due to aging, corrosion, wear, or damage. Regular reanalysis ensures that the gross capacity remains an accurate representation of current safety limits.

Capacity can decrease over time due to aging or damage; reanalysis helps maintain safety.

What if gross load exceeds gross capacity?

If the gross load exceeds gross capacity, immediate action is required. Typical actions include reducing the load, reinforcing the structure, or redesigning the element to restore an adequate margin.

Exceeding capacity means you must reduce load or strengthen the system.

Top Takeaways

- Compute gross load as the sum of all applicable loads.

- Use gross capacity as the design limit defined by codes and materials.

- Always compare load to capacity with a safety margin.

- Document assumptions, methods, and factors of safety.

- Communicate results clearly to all stakeholders.