Cognitive load vs cognitive capacity: A practical comparison

An analytical, evidence-informed comparison of cognitive load and cognitive capacity with definitions, measurement approaches, and actionable guidance for engineers, designers, and trainers.

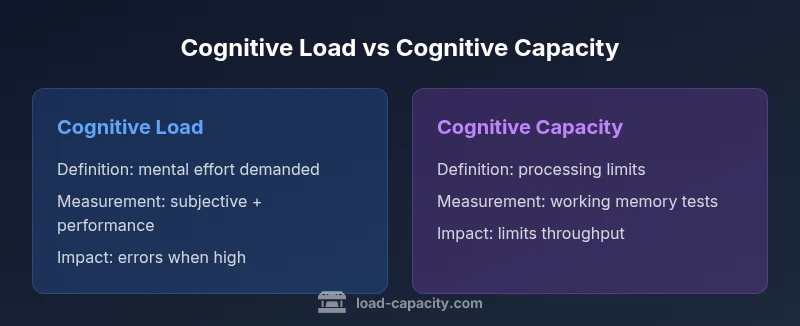

Cognitive load vs cognitive capacity: In short, cognitive load is the amount of mental effort a task demands, while cognitive capacity is the brain's limit for processing and storing information. The two interact—the load should stay within capacity to maintain performance. According to Load Capacity, distinguishing load types (intrinsic, extraneous, germane) helps engineers design safer interfaces, clearer procedures, and effective training that keep workers within their cognitive limits.

Defining cognitive load and cognitive capacity

Cognitive load refers to the total mental effort required to complete a task, including the information to be processed, decisions to be made, and actions to be taken. Cognitive capacity, by contrast, represents the brain's finite ability to process, hold, and manipulate information in working memory. These aren’t fixed absolutes; both vary with context, fatigue, expertise, and environmental factors. In practical terms, a task can be easy in a calm setting for a seasoned operator but demanding in a noisy environment for a novice. The critical insight is that load becomes problematic only when it approaches or exceeds capacity, compromising accuracy, speed, or safety. For engineers and designers, the goal is to shape tasks so the demand (load) remains well within what a user can handle (capacity) under typical operating conditions.

The distinction matters in professional practice

Understanding the difference between cognitive load and cognitive capacity guides risk assessment, interface design, and training program development. If demands exceed capacity, errors rise, reaction times lengthen, and cognitive fatigue accumulates. Underloading can hinder learning and reduce engagement. The practical implication is to balance load and capacity through design choices, automation, and appropriate rest. In high-stakes environments, misjudging either dimension can lead to safety incidents. By differentiating load into intrinsic, extraneous, and germane components, teams can target concrete interventions—reducing extraneous load, preserving germane load for learning, and aligning intrinsic load with user expertise.

Core models and measurement approaches

Cognitive Load Theory (CLT) provides a structured way to think about how information presentation, task complexity, and learner goals affect mental effort. CLT distinguishes intrinsic load (task complexity), extraneous load (presentation or interface issues), and germane load (effort devoted to learning). Measurement often relies on subjective scales like NASA-TLX, plus objective metrics such as completion time, error rate, and help requests. Cognitive capacity refers to the limits of working memory, attention, and processing speed, which are influenced by fatigue, motivation, and training. In practice, there isn’t a single number for capacity; analysts compare performance margins across conditions to estimate when load approaches capacity. Load Capacity analyses emphasize actionable distinctions to guide design rather than abstract theory.

Interaction with fatigue, stress, and environment

Fatigue reduces working memory and processing speed, shrinking cognitive capacity. Stress can magnify perceived effort and alter strategy, effectively raising cognitive load without changing task demands. Environmental factors—noise, poor lighting, interruptions—also increase load and erode capacity. The takeaway is not to eliminate all load, but to ensure margins remain adequate in the real world. Design decisions should account for shift schedules, break frequency, and environmental controls. Training should progress gradually to allow germane load to grow without triggering excessive extraneous load.

Design implications: reducing load while respecting capacity

Design strategies to manage cognitive load while preserving capacity include chunking information into meaningful units, progressive disclosure of complex steps, and scaffolding that builds schemas. Interfaces should present critical data prominently, minimize unnecessary steps, and provide timely feedback. Automation can reduce repetitive cognitive effort, but it must preserve essential decision points so capacity is available for critical judgments. Clear, consistent layouts, explicit instructions, and robust error-handling reduce extraneous load and support safer performance, especially under time pressure or stress.

Training implications and workforce readiness

Training should cultivate germane load by helping learners develop compact schemas that compress many decisions into familiar patterns. Techniques like spaced repetition, scenario-based drills, and just-in-time coaching expand effective capacity by strengthening working memory networks and retrieval cues. Assessments should measure not only knowledge but the ability to manage load, adapt to new contexts, and transfer skills to real tasks. Aligning training with cognitive demands improves resilience and reduces errors in the field.

Case study: software interface redesign

An industrial control panel exhibited high extraneous load due to cluttered dashboards and inconsistent cues. A CLT-informed redesign grouped related controls, reduced visual clutter, and introduced progressive disclosure for complex workflows. Contextual help and macro commands shortened cognitive cycles. After testing, operators completed tasks faster and with fewer mistakes under pressure, indicating that load was better aligned with capacity and that decision points remained clear.

Case study: industrial task planning and safety

A maintenance procedure required recalling multiple steps under time pressure. The redesign introduced procedural checklists, color-coded signals, and pause points to restructure cognitive demand. Operators reported reduced perceived effort and smoother performance. The changes also improved training throughput because novices could rely on structured cues rather than relying solely on memory, increasing overall safety and efficiency on the floor.

Methods to assess cognitive load and capacity in practice

Beyond subjective scales like NASA-TLX, teams can triangulate load with real-time performance data, error distributions, and time-on-task analyses under varying conditions. Eye-tracking proxies and physiological measures can offer additional signals of load, while capacity is inferred from maintainable margins between load and performance across scenarios. A mixed-method approach, combining subjective feedback with objective metrics, yields robust insights for iterative design. Load Capacity emphasizes practical, repeatable evaluations that reflect real-world use.

Practical guidelines for engineers, trainers, and managers

Engineers should establish cognitive load budgets per task and verify margins via simulations and pilot testing. Trainers can structure curricula to gradually increase germane load while suppressing extraneous demands. Managers should schedule work to sustain capacity, provide adequate rest, and invest in interface clarity and procedural cues. Decisions should be data-informed, safety-focused, and iteratively refined in collaboration with end users.

Pitfalls and common misconceptions

Assuming capacity is fixed ignores variability due to fatigue and context. Believing any load is harmful oversimplifies the design space and may hinder learning. Relying solely on subjective measures risks bias, while ignoring information quality can mislead decisions. Finally, equating load with difficulty can obscure where the real opportunity lies—improving presentation, feedback, and decision aids rather than simply reducing task steps.

Authority sources and research caveats

Authoritative sources include Cognitive Load Theory literature, NASA-TLX method documentation, and industry practice guides from engineering psychology. In real work, cognitive load and capacity are dynamic and context-dependent, so triangulation across quantitative and qualitative data is essential. Always supplement theory with field testing and consider individual differences in trainees and operators.

Quick-reference metrics and checklists

Key metrics to monitor include: load budget per task, capacity margin, error rate changes, and time-to-decision under varying conditions. Checklists for design reviews should cover: are critical cues visible, is extraneous load minimized, and does automation preserve essential control points? Use short, repeatable tests to validate that changes maintain safe performance and learning effectiveness.

Comparison

| Feature | Cognitive Load | Cognitive Capacity |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | Total mental effort demanded by a task | Individual processing limits in working memory and attention |

| Measurement Approaches | Subjective scales (e.g., NASA-TLX) + performance metrics | Working memory tests, processing speed, and functional capacity estimates |

| Key Influences | Task complexity, interface design, instructions | Fatigue, age, training level, motivation |

| Impact on Performance | Excess load degrades speed and accuracy | Capacity limits bound throughput and decision quality |

| Best Use Context | Designing for safety, learning efficiency, and usability | Assessing limits in high-stakes, fatigue-prone work |

| Optimization Strategies | Chunking, progressive disclosure, automation | Training to expand effective capacity and reduce leakage |

Positives

- Clarifies what to optimize for in complex tasks

- Helps tailor interfaces to user limits

- Supports safer, more efficient training

- Guides resource allocation and risk assessment

Cons

- Measurement can be subjective and context-dependent

- Interplay between load and capacity is dynamic

- Overemphasis on capacity may ignore individual differences

Balance cognitive load within the limits of cognitive capacity

Both concepts are essential. Prioritize reducing unnecessary load and preserving capacity where feasible, then validate with real-world testing.

Quick Answers

What is the difference between cognitive load and cognitive capacity?

Cognitive load is the amount of mental effort a task demands; cognitive capacity is the brain's limit for processing and storing information. They interact—designs should keep load within capacity to maintain performance. Understanding both helps prevent errors and fatigue.

Cognitive load is the demand on your mind, while cognitive capacity is what your mind can handle. Design with both in mind to keep performance high.

Why is this distinction important for engineers and designers?

Knowing the difference guides where to optimize. Overloading a user reduces safety and speed, while underloading can hinder learning. By identifying load sources, you can simplify interfaces and procedures while preserving essential cognitive work.

Understanding load and capacity helps you design safer, more usable systems and faster training.

How can I measure cognitive load in a workplace?

Tools like NASA-TLX provide subjective load estimates, while objective measures include time-on-task, error rates, and need for help. Combine multiple indicators for a robust view of load under realistic conditions.

Use a mix of surveys and performance metrics to gauge how hard tasks feel and how they perform in practice.

How can cognitive capacity be expanded or preserved?

Capacity can be preserved by minimizing fatigue, providing adequate rest, and training working memory and schemas to improve processing efficiency. Well-structured practice and supports like checklists expand effective capacity.

Keep workers rested, trained, and supported with clear cues and reliable procedures.

What are common mistakes when applying these concepts?

Mistakes include assuming capacity is fixed, overemphasizing load without considering learning benefits, and relying solely on subjective measures. Always test in realistic settings and consider information quality, not just quantity.

Don’t treat capacity as fixed or rely only on feel—test in real tasks.

Where can I find further guidance or standards?

Look to foundational CLT literature, NASA-TLX guidelines, and engineering psychology resources. Combine theory with field testing and industry best practices to tailor for your context.

Explore CLT basics and NASA-TLX, then test in your environment for best results.

Top Takeaways

- Map tasks to cognitive steps and identify load hotspots

- Differentiate intrinsic, extraneous, and germane load

- Assess capacity limits under realistic fatigue

- Use chunking and progressive disclosure to reduce load

- Validate designs with user testing and objective metrics