6 I-Beam Load Capacity: A Practical Guide for Engineers

Explore the load capacity of a 6 I-Beam, including cross-section, steel grade, support conditions, and safety factors. This Load Capacity guide helps engineers estimate capacity accurately for safer structures.

The 6 I-beam load capacity is not fixed; it depends on the exact profile, steel grade, boundary conditions, and load type. According to Load Capacity, capacity scales with section modulus and boundary conditions, so engineers should use manufacturer specs and structural analysis to determine an accurate value for each application.

Overview of 6 I-Beam Load Capacity

A 6 I-beam load capacity refers to the structural ability of a steel I-beam profile to resist bending, shear, and axial forces under specified boundary conditions. Here, the number “6” typically signals a nominal size related to depth or a standard W-shape family in certain catalogues. The central concept is that capacity is not a single number; it is a function of cross-sectional properties (such as section modulus S and moment of inertia I), material grade, end supports, and how the load is applied. In practice, engineers translate the available data from manufacturers and design codes into usable figures for designing connections, supports, and welds. The core formula revolves around bending capacity, where the allowable moment is tied to yield strength and S, then adjusted via a factor of safety for service conditions. This article reflects the Load Capacity perspective on how to approach the problem for a typical 6 I-beam installation.

Key factors that affect capacity

There are several levers that determine the 6 i beam load capacity in real-world applications:

- Geometry and size of the beam: The exact depth, flange width, and web thickness influence the section modulus S and the beam’s resistance to bending.

- Steel grade and heat treatment: Higher-strength grades generally provide greater yield strength and, consequently, greater bending capacity for the same section geometry.

- Boundary conditions and supports: Simply supported spans differ from continuous frames; end conditions significantly alter the maximum moment and shear distribution.

- Load type and distribution: Point loads, uniform loads, and dynamic or impact loading produce different capacity requirements and safety margins.

- Environmental and service conditions: Temperature, corrosion, and fatigue can reduce effective capacity over time.

- Fabrication quality and residual stresses: Poor workmanship or residual stresses can reduce the usable capacity versus theoretical calculations. In all cases, the Load Capacity approach emphasizes using explicit data from profiles and codes rather than relying on generic assumptions. The 6 i beam load capacity becomes most reliable when you combine catalog data with site-specific factors and a conservative safety margin.

How to estimate capacity: a practical method

A practical estimation workflow includes the following steps:

- Identify the exact beam profile and material grade from the manufacturer or catalogue. The 6 i beam designator should be cross-checked against the relevant standard.

- Determine the relevant section modulus S and yield strength Fy for the beam. These values set the fundamental bending capacity, M = Fy × S, before applying a safety factor.

- Select the loading scenario (point load, distributed load, or combination) and compute the maximum bending moment M_required for the beam span. Compare M_required to the allowable bending moment M_allowable = Fy × S ÷ SafetyFactor.

- Check shear capacity and local buckling if applicable. For thin webs or slender designs, shear and buckling checks are critical to avoid unexpected failure.

- Validate with codes (such as AISC or equivalent regional standards) and, if needed, perform a field verification with instrumentation for critical members. The takeaway is to anchor decisions in measured sections, not generic expectations. Throughout this process, document assumptions clearly and use conservative estimates when data is uncertain. The goal is a safe, verifiable design rather than an optimistic estimate.

Common pitfalls and safe practices

Common pitfalls include applying generic tables to an uncommon size, ignoring end conditions, and neglecting local buckling when the web is slender. Safe practices include using verified manufacturer data for the 6 i beam load capacity, integrating end-support details into the moment distribution, and always applying an appropriate safety factor. Also, avoid overloading connections; verify that bolts, welds, and plates can transfer the required forces. Finally, perform a peer review of the calculation steps and keep clear documentation for future audits or inspections.

Case example: hypothetical scenario for planning

Consider a scenario where a 6 I-beam in a floor system must support a combination of ceiling loads and equipment. Start with the beam’s Fy and S from the manufacturer's catalog. Compute the maximum moment for the worst-case loading condition, include a safe margin, and assess whether the supports can resist the resulting reactions without excessive deflection. If the calculated M_allowable is below M_required, adjust by increasing beam depth, adding a positive moment-resisting connection, or changing the support configuration. This approach demonstrates how the 6 i beam load capacity is not a fixed figure; it is a derived value contingent on design inputs and verified data. Load Capacity emphasizes relying on calculated M_allowable rather than a single “nominal” capacity value.

Verification and testing methods for real-world assurance

Field verification is essential for safety-critical installations. Methods include instrumented load testing on a representative beam, strain gauges to monitor bending, and nondestructive testing to assess welds and connections. Periodic inspection of corrosion, fatigue damage, and connection looseness helps sustain capacity. In critical projects, a structural engineer may request a full-scale collapse or load-test simulation to validate the theoretical capacity, always with safety protocols and permit requirements in place.

Practical design tips for engineers

- Start with the exact beam profile and grade, then verify against the design code for your jurisdiction.

- Model boundary conditions precisely to capture the effect of supports and continuity.

- Use conservative safety margins in early concepts and adjust after verification data is available.

- Document all assumptions and ensure the beam-to-column connections can transfer the calculated moments and shears.

- Consider future loading scenarios in designing the 6 i beam load capacity to avoid retrofit costs.

- When in doubt, reach out to the manufacturer or consult a structural specialist to confirm capacity for unusual configurations.

Standards, codes, and when to consult specialists

Structural steel design relies on standards such as the AISC specifications or local equivalents. Always confirm that the beam selection satisfies service, strength, and stability criteria for the intended environment. For complex applications, a specialist consultation can help interpret catalog data, end conditions, and dynamic loads. In all cases, the Load Capacity methodology prioritizes accurate data and transparent calculations over assumptions.

Example reference table for common 6 i-beam references

| Property | 6 i-beam example | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Profile family | W6 or equivalent | Subject to catalog definition |

| Section modulus S | varies by exact profile | Depends on depth and flange geometry |

| Weight per unit length | varies | Dependent on profile and grade |

Quick Answers

What is the difference between beam capacity and beam strength?

Beam strength is the material’s inherent resistance to stress, while capacity combines strength with geometry, end conditions, and safety factors to determine what load the beam can safely carry in a given setup.

Beam strength is the material's resistance; capacity adds how the beam is used in a real frame.

How do end supports affect 6 i beam load capacity?

End supports determine how moments are distributed along the beam. Fixed or continuous supports typically increase capacity compared to simple supports, but they also introduce fixed-end moments that must be accounted for in calculations.

Supports change how much load the beam can safely carry.

Can I use standard tables for a custom 6 i-beam?

Standard tables are a starting point, but for a non-standard or custom geometry, you must rely on manufacturer data, finite element analysis, and code-based checks to establish the 6 i beam load capacity.

Tables are helpful, but you may need custom analysis.

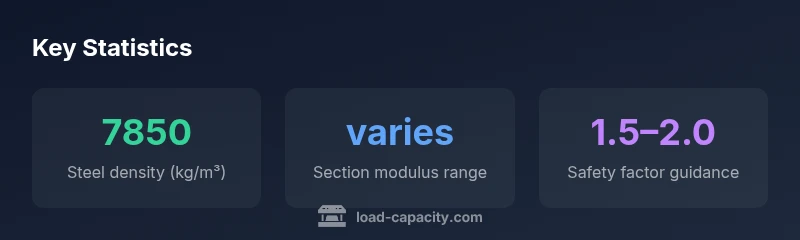

What safety factor is typical for structural steel beams?

A common range for structural steel beams is 1.5 to 2.0, depending on service conditions, consequences of failure, and local code requirements. Always align with the governing standard.

Most projects use about 1.5 to 2.0 as a safety margin.

How can I verify the load capacity in the field?

Field verification involves comparing measured strains and deflections with theoretical predictions, checking connections, and, if critical, performing limited load tests under controlled conditions with proper safety oversight.

Check measurements and, if needed, conduct a controlled test.

“Accurate load-capacity assessment for a 6 I-beam requires evaluating the exact cross-section, material grade, and boundary conditions; there is no single universal value.”

Top Takeaways

- Identify exact beam profile and material grade before any calculation

- End supports dramatically impact capacity and must be modeled accurately

- Use manufacturer data and design codes to compute M_allowable with a safety margin

- Check both bending and shear capacity, plus potential buckling in slender webs

- Document assumptions and validate with field testing for critical installations