Payload vs Load Capacity: An Engineer's Practical Guide

An analytical comparison of payload vs load capacity by Load Capacity. Learn definitions, measurement basics, safety margins, and planning tips for engineers and fleet managers.

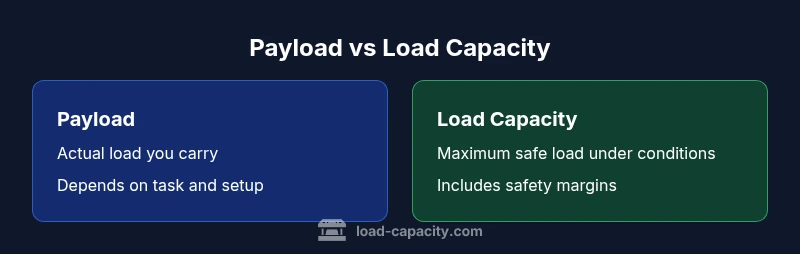

Payload vs load capacity are related but distinct: payload is the actual load you plan to carry; load capacity is the maximum safe load the system can support. Knowing both helps prevent overload, guides design choices, informs maintenance, and supports regulatory compliance during audits today and for future planning.

Understanding the Core Concepts: payload vs load capacity

Payload vs load capacity are foundational terms in engineering practice and field operations. In essence, payload describes the actual mass or force you intend to move or carry during a task, while load capacity represents the upper limit that a vehicle, structure, or component can safely withstand under defined conditions. According to Load Capacity, clarifying these concepts early reduces misinterpretations and sets the stage for accurate planning, testing, and verification. The two metrics are not interchangeable, but they are tightly linked: a system’s payload is a subset of its load capacity, and successful planning requires that the payload never approaches the capacity limit. When teams understand this relationship, they can allocate resources, specify equipment, and schedule maintenance with confidence. Across industries—automotive, construction, aerospace, and manufacturing—the distinction informs everything from route selection to structural health monitoring. A precise definition also streamlines communication with stakeholders, auditors, and regulatory bodies, which is essential in safety-critical domains where margins matter. In short, payload and load capacity are two sides of the same safety coin, guiding how much load is acceptable in practice.

Why the Distinction Matters in Engineering and Maintenance

In many projects, engineers grapple with planning, procurement, and maintenance decisions that hinge on correctly distinguishing payload from load capacity. The payload reflects the actual demand placed on a system—trucks carrying concrete, cranes lifting steel, or shelves bearing pallets. Load capacity, by contrast, is a rating set by design limits, safety factors, and testing results. This distinction matters for several reasons:

- Safety: Exceeding load capacity is a primary failure mode for structures and equipment, risking collapse or abrupt malfunction.

- Compliance: Regulations and codes typically require explicit limits and documented safety factors; conflating terms can lead to audits failing or penalties.

- Lifecycle planning: Knowing both metrics supports maintenance scheduling, wear assessment, and retrofit decisions as loads evolve.

- Procurement clarity: Buyers can compare equipment not just by payload but by how the capacity accommodates peak operating scenarios and future needs. To prevent errors, organizations should adopt consistent terminology, document the context (static vs dynamic loads), and align with product manuals and standards. The Load Capacity team recommends establishing a glossary, mapping each asset’s payload to its rated load capacity, and ensuring all project stakeholders reference the same definitions. This shared language improves risk management and decision quality across teams.

Measurement Foundations: Defining Units, Standards, and Context

Accurate measurement of payload and load capacity depends on clear unit definitions, standard reference conditions, and context-specific labeling. Payload is typically expressed in mass units such as kilograms or pounds, reflecting the force or gravitational load the object represents. Load capacity can be expressed as mass (kg or lb) or as a structural limit expressed in terms of bending moments or stress limits, depending on the system’s design. Standards for measuring and reporting these values vary by industry but usually specify:

- Reference state: vehicle or structure in its typical operating configuration (unloaded, with standard ballast, etc.).

- Temperature, speed, and dynamic effects: many capacities change with temperature, vibration, or motion; certified testing often includes these factors.

- Safety factors: margins are applied to ensure performance under uncertain conditions; these factors should be clearly documented and justified.

- Documentation: manufacturers and engineers must provide data sheets that define units, test methods, and interpretation guidance. In practice, teams should harmonize units across systems and maintain a traceable chain of documentation from test labs to on-site usage. Adopting consistent labels—payload, gross payload, and system load capacity—reduces confusion and supports cross-functional collaboration with procurement, safety, and regulatory teams. The goal is a transparent, auditable framework where everyone understands how numbers were obtained and what they imply for daily operations.

How Payload Is Used in Planning, and Where Load Capacity Applies

Planning a task begins with the payload: what you intend to move or perform, including all sub-loads such as tools, accessories, and consumables. For vehicle routings, the payload determines the choice of vehicle, route planning, and fuel budgeting. In contrast, load capacity is the ceiling that prohibits exceeding safe limits, influencing how you stage operations, distribute weight, and sequence tasks. For instance, a crane’s payload rating dictates the maximum lift under specified conditions, but the crane’s structural load capacity governs the safe load the supporting structure can bear. The distinction matters for reliability and safety: a high payload alone is meaningless if the load capacity cannot sustain the peak dynamic forces during movement. Project teams should map payload scenarios to the corresponding load-capacity limits, and use a margin for error in planning. This alignment supports safer work orders, clearer maintenance expectations, and better risk management when conditions change—such as weather, terrain, or equipment wear. In short, payload guides what you do; load capacity guards how safely you do it.

Structural Context vs Vehicle Context: Different Interpretations Across Domains

Different disciplines treat payload and load capacity through slightly different lenses. In transportation and manufacturing, payload is often tied to operational planning, customer requirements, and payload distribution across axles or pallets. Structural engineering, however, emphasizes load capacity as a design constraint governing member sizing, connection details, and service life expectations. Bridges and buildings rely on load capacity ratings that account for live loads, dead loads, environmental effects, and seismic or wind forces. Vehicles emphasize payload distribution, stabilization, and center-of-gravity considerations to prevent rollover or loss of control. The common thread is that both metrics must be evaluated in the context of the intended use, safety regulations, and service conditions. Practically, this means engineers should specify both numbers in design documents, verify their relationship through simulations or tests, and communicate limits clearly to operators and maintenance crews. The goal is a consistent methodology that aligns performance with safety across all contexts.

Calculation Approaches: From Simple Rules to Dynamic-Load Realities

Calculating payload and load capacity involves both straightforward rules and more sophisticated analyses. A basic approach starts with known ratings in product manuals: payload is the mass you plan to move, while load capacity is the maximum permissible load under defined conditions. For static planning, this suffices, but real-world operations introduce dynamic effects. Dynamic loads—the peak forces during acceleration, braking, or impact—can significantly alter the effective capacity. Therefore, engineers often apply safety factors or de-rate the capacity to account for these effects. In design and certification, finite element analysis, dynamic testing, and scenario-based simulations are used to verify margins under representative conditions. A robust methodology tracks assumptions—such as temperature, speed, and load distribution—and includes them in the final documentation. When comparing options, consider both payload and load-capacity ratings under the same reference conditions, and make explicit any safety factors used. This rigorous approach reduces surprises during operation and supports regulatory compliance.

Practical Examples Across Vehicles, Equipment, and Structures

Real-world examples illustrate how payload and load capacity interact in daily work. A delivery truck might have a specified payload of 2,000 kg, but its load-capacity rating for the frame and suspension could be 2,500 kg to accommodate dynamic loads safely. A gantry crane might lift up to a 10-ton rated payload, yet the supporting structure’s capacity and anchorage determine the maximum sustainable load during peak winds or tremors. In building design, engineers specify dead loads and live loads, ensuring the structure’s load capacity remains well above expected payloads with adequate safety margins. These examples show that: the payload determines what you attempt to move, while load capacity enforces the safety envelope around that movement. For procurement, teams should look for equipment whose load capacity significantly exceeds the expected payload, with documented safety factors and testing data. This practice reduces risk and extends the service life of assets.

Safety Margins, Codes, and Verification Steps

Safety margins are central to both payload planning and load-capacity verification. Codes and standards require explicit declarations of load limits and margins. Verification steps typically include labeling, training, and routine inspections to ensure that actual loads do not approach rated limits. Documentation should capture the reference conditions, measurement units, and test results. Audits often examine whether the declared payload, grade, and capacity align with the asset’s design envelope and whether safety factors have been appropriately applied. Verification isn’t a one-off task; it’s an ongoing discipline that informs maintenance cycles, replacement schedules, and operator training. In practice, organizations should implement a standard template for load calculations that cross-references payload scenarios with relevant load-capacity limits. This approach ensures consistent decision-making and reduces the likelihood of human error in high-stakes environments.

How to Document and Communicate Assumptions for Audits and Procurement

Effective documentation of payload and load capacity relies on clarity and accessibility. Projects should maintain a centralized data package that includes: the payload definition, the load-capacity rating, the reference conditions, safety factors, and verification results. All figures should be traceable to test reports or manufacturer data sheets, with dates clearly indicated. Communication is equally important: operators need straightforward guidance on how to apply the ratings in practice, while engineers require precise notes for audits and future retrofits. Clear diagrams of load distribution, weight breakdowns, and center-of-gravity considerations help non-technical stakeholders understand constraints. The Load Capacity team emphasizes the value of a living document that updates ratings as assets wear or replacements occur, ensuring procurement decisions reflect current realities and regulatory requirements.

Comparison

| Feature | Payload | Load Capacity |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | The actual load you plan to carry in operation | The maximum safe load the system can support under defined conditions |

| Units/Measurement | Mass (kg or lb) for the carried load | Mass or force (kg, lb) or bending moment depending on context |

| Context of Use | Operational planning for loads to move or carry | Design, safety, and compliance limits for the system |

| Safety Margin | Often specified with a margin; varies by application | Incorporates safety factors for static and dynamic loads |

| How Calculated | Specified by manufacturer or operating limits | Derived from structural ratings, safety factors, and testing |

| Best For | Operational planning and workflow management | Engineering design and regulatory certification |

Positives

- Clarifies planning by separating load demands from system limits

- Improves safety by enforcing measurable margins

- Supports regulatory compliance and audit readiness

- Aids procurement decisions with clear rating context

Cons

- Can be confusing if terms are not defined consistently

- Requires additional calculations and documentation

- May appear conservative, affecting cost or efficiency

Payload and load capacity are distinct but complementary metrics; use both for safe, compliant operations

Understanding both metrics prevents overloading and guides design, procurement, and maintenance decisions. When planning, verify that the payload fits within the system's load capacity under expected dynamic conditions.

Quick Answers

What is payload?

Payload is the actual load carried or moved in operation, excluding the host vehicle's weight. It represents the demand placed on the system.

Payload is the load you carry during operation.

What is load capacity?

Load capacity is the maximum safe load the system can support under defined conditions, including safety margins and potential dynamic effects.

Load capacity is the maximum safe load the system can handle.

Is payload the same as gross vehicle weight?

No. Gross vehicle weight is the sum of curb weight, payload, and other loads. Payload is the portion of GVW attributable to the carried mass, while GVW represents total weight.

GVW is the total weight; payload is part of that total.

How do I calculate payload on a vehicle?

From the vehicle’s GVWR, subtract the curb weight to obtain payload. Ensure the resulting value remains within the stated load capacity margins.

Payload equals GVWR minus curb weight.

Do dynamic loads change the capacity?

Yes. Dynamic loads can increase peak forces; always apply safety factors or de-rate capacity to account for these effects.

Dynamic loads matter; plan for them with safety margins.

Top Takeaways

- Define payload and load capacity clearly before planning

- Account for dynamic loads and safety factors in calculations

- Document assumptions to support audits, procurement, and maintenance

- Choose equipment with a load capacity exceeding planned payload

- Communicate limits clearly to engineers, operators, and managers