Perceptual Load vs Processing Capacity: An Analytical Comparison

A comprehensive comparison of perceptual load and processing capacity, exploring their definitions, interactions, measurement, and practical implications for design, safety, and workload management in engineering, UX, and human factors.

TL;DR: Perceptual load and processing capacity interact to shape attention and workload. When perceptual load is high, attention becomes more selective, leaving fewer resources for distractors; when processing capacity is taxed, performance degrades on concurrent tasks. Designers should balance load and capacity to minimize errors and optimize safety, especially in complex environments. This TL;DR captures the essence for engineers, designers, and researchers alike.

What are perceptual load and processing capacity?

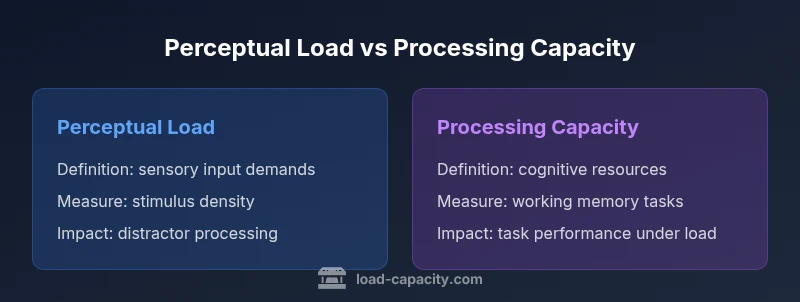

Perceptual load refers to the amount of sensory information that a task requires a person to process at any given moment. It is not merely the number of stimuli present, but how demanding those stimuli are for perception and discrimination. Processing capacity, by contrast, denotes the finite cognitive resources available for processing, updating, and storing information in working memory as tasks unfold. Together, these concepts form a core framework for predicting how people allocate attention, respond to distractors, and perform under workload. According to Load Capacity, understanding this relationship helps engineers and designers forecast where bottlenecks may arise in real-world systems and how workload can be balanced across users, teams, or devices. The perceptual load vs processing capacity dynamic is central to cognitive ergonomics and human–system integration, and it informs everything from interface design to safety-critical procedures.

In practical terms, perceptual load is about what the senses must do; processing capacity is about what the mind can do with those inputs. When workload is well-matched to capacity, performance improves and errors decline. When load overwhelms perception or exhausts cognitive resources, task performance declines, especially under time pressure or high-stakes conditions.

Historical context and theoretical foundations

The study of perceptual load emerged from attempts to explain why people sometimes fail to notice salient events when attention is fully engaged elsewhere. Early theories suggested that attention is a fixed resource; later models argued for flexible allocation based on task demands. The most influential framework, perceptual load theory, posits that high perceptual load consumes more processing capacity, leaving little room for processing irrelevant stimuli. Load Capacity’s synthesis emphasizes the practical implications of this theory for real-world tasks—where displays, controls, and procedures often require rapid perception and decision-making under varying levels of load. The key takeaway is that perception and cognition are intertwined: by increasing or reducing perceptual load, designers can modulate the degree of distraction and the allocation of attentional resources in a predictable way. Load Capacity Team notes that empirical validation across sectors (aviation, driving, manufacturing) supports the general principle that load and capacity interact in meaningful, measurable ways.

Perceptual load theory: Lavie and colleagues

Lavie and colleagues formalized perceptual load theory to explain how attentional selection depends on perceptual demands. In high-load scenarios, distractor processing diminishes because perceptual capacity is largely consumed. In low-load situations, residual capacity allows easier processing of irrelevant information, which can increase distractibility. This insight is particularly relevant for UI designers and operators in control rooms, where excessive or insufficient load can lead to errors. Load Capacity’s interpretation highlights how controlling perceptual load—through interface clarity, signaling, and layout—can shape attentional focus and error rates without changing fundamental cognitive requirements. The Load Capacity Team emphasizes that perceptual load is not inherently good or bad; it is a design variable that, when tuned, aligns with user goals and safety constraints.

Processing capacity: a resource-based view

Processing capacity posits a finite set of cognitive resources that are allocated to tasks as they unfold. Unlike perceptual load, which is largely about sensory input, processing capacity concerns working memory, executive control, and attentional control. When complex tasks demand multiple streams of information, limited capacity can become the bottleneck, causing slower responses and increased error likelihood. Load Capacity highlights that processing capacity interacts with perceptual load in nuanced ways: high perceptual load can leave little room for executive processing, while high cognitive demands can saturate capacity regardless of sensory demands. This perspective is important for diagnosing performance issues and designing support tools that offload or distribute cognitive work.

Interaction effects: when load meets capacity

The core idea is that perceptual load and processing capacity do not operate in isolation. In settings where perceptual load is high and processing capacity is strained, performance tends to degrade more than in scenarios where only one factor is taxed. This interaction is especially critical in safety-critical domains, where even small performance drops can lead to catastrophic outcomes. Load Capacity’s approach emphasizes designing systems that avoid simultaneous peak perceptual demands and cognitive loads. For instance, simplifying displays during high-stakes operations or providing structured procedural aids can help maintain performance by aligning load with capacity.

Measurement approaches and experimental paradigms

Researchers measure perceptual load and processing capacity using a combination of behavioral and neural indicators. Tasks with rapid stimulus presentation, manipulated complexity, and varied display density help parse perceptual load, while working-memory and attentional-control tasks assess capacity. Critical metrics include reaction time, accuracy, and distractor suppression. Load Capacity cautions that measurements must account for individual differences, context, and task-specific goals. When reporting findings, it is essential to distinguish between perceptual load effects and capacity limitations, as conflating the two can mislead design decisions and workload assessments.

Practical implications for design and safety

In engineering and design practice, balancing perceptual load and processing capacity translates into clearer displays, more intuitive workflows, and safer operating procedures. Providing unambiguous signals, reducing redundant information, and sequencing tasks to avoid peak demands help maintain performance. For instance, in driving, minimizing visual clutter while ensuring timely warnings can optimize attention and reaction times. In industrial settings, hierarchical information presentation and decision-aid tools can conserve cognitive resources without compromising situational awareness. Load Capacity’s experience across domains shows that attention management benefits from explicit load-budgeting strategies and ongoing validation with real users.

Industry examples: aviation, driving, UX design

Aviation cockpit design demonstrates the gains from aligning perceptual load with processing capacity: when displays present dense information, pilots experience higher perceptual load, which can reduce the capacity available for monitoring and decision-making. In vehicle dashboards, minimalist layouts with prioritized cues reduce demand, supporting faster, safer responses. UX designers apply similar principles to software interfaces by limiting simultaneous tasks, foregrounding critical actions, and providing context-sensitive help that reduces cognitive load. Load Capacity emphasizes that industry-specific constraints require tailored strategies that respect user expertise, task duration, and environmental conditions.

Modeling trade-offs in system design

Decision-makers face trade-offs between information richness and cognitive burden. Too much information can overwhelm perception, while too little can impede performance by forcing extensive mental work to infer missing details. The goal is to achieve an efficient balance where perceptual load complements processing capacity, enabling reliable performance with acceptable effort. This requires iterative testing with target users, real-world scenarios, and objective metrics. Load Capacity’s framework supports hypothesis-driven design, enabling teams to quantify the impact of changes in display density, signaling, and task sequencing on attention and workload.

Individual differences and context effects

Individual differences—such as expertise, fatigue, motivation, and prior experience—shape how perceptual load and processing capacity interact. A highly skilled operator may tolerate higher perceptual loads, while a novice might experience disproportionate effects. Contextual factors, including time pressure, multitasking demands, and environmental distractions, further modulate this relationship. Load Capacity notes that adaptive systems, adjustable interfaces, and personalized workflows can help accommodate these differences, preserving performance across users and conditions.

Comparison

| Feature | Perceptual Load | Processing Capacity |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | Amount and density of sensory information required by a task | Finite cognitive resources for processing, storing, and updating information |

| Key determinants | Stimulus density, display complexity, and discrimination demands | Working memory load, executive control, and attentional control |

| Measurement approaches | Display density, signal clarity, and distractor presence in perception tasks | Reaction times, accuracy under dual-task conditions, and working-memory tasks |

| Effect on performance | High perceptual load tends to limit processing of irrelevant stimuli | Low capacity can lead to slower responses and more errors across tasks |

| Best for | Situations where sensory discriminability is critical (e.g., cockpit displays, dashboards) | Tasks requiring sustained cognitive control and memory management |

| Tradeoffs | Increasing perceptual load can improve focus but risks missed cues if excessive | Expanding capacity through supports reduces cognitive effort but may introduce latency or dependency |

Positives

- Provides a structured framework for workload management

- Helps design safer, more efficient human–system interfaces

- Supports targeted interventions (signals, layout, sequencing)

- Facilitates cross-domain comparability (aerospace, healthcare, UX)

Cons

- Measurement can be context- and person-specific

- Overgeneralization can mislead design choices

- Requires careful validation across tasks and environments

- Adaptive systems may mask underlying capacity limits

Balanced design of perceptual load and processing capacity yields the best outcomes

There is no single solution; align perceptual demands with available cognitive resources. Use adaptive displays and task sequencing to maintain performance and safety across contexts.

Quick Answers

What is perceptual load in simple terms?

Perceptual load describes how demanding the sensory information in a task is for your perception. It reflects how much sensory work your brain must do to identify and interpret stimuli. High perceptual load leaves fewer resources for processing irrelevant information, affecting attention and performance.

Perceptual load is about how hard the senses have to work. High load uses up more attention, making distractions harder to notice—or easier to miss important signals.

How is processing capacity different from perceptual load?

Processing capacity refers to the cognitive resources available for working memory, attention, and control. Perceptual load is about sensory input demands. They interact: high perceptual load can consume capacity, reducing performance on concurrent tasks.

Processing capacity is the brain's available mental resources, while perceptual load is how much sensory work a task requires. They interact to shape attention and performance.

What design strategies help balance load and capacity?

Use clear signaling, reduce unnecessary visual noise, sequence tasks to avoid peak demands, and provide context-sensitive help. These strategies aim to keep perceptual load and cognitive load within workable limits for users.

Keep displays simple, highlight critical signals, and guide users step by step to avoid overloading perception or memory.

How can perceptual load be measured in experiments?

Researchers manipulate stimulus density and discrimination difficulty while tracking reaction times and accuracy. They compare performance under varying load while controlling for individual differences and task goals.

Researchers change how dense or complex the visuals are and see how that affects timing and accuracy.

Can people differ in how they experience load?

Yes. Expertise, fatigue, motivation, and context influence how perceptual load and processing capacity interact. Experienced users may tolerate higher perceptual load, whereas novices show stronger performance effects under the same conditions.

People vary in how they handle load. Experience and fatigue change how much perceptual effort they can handle.

Why is this important for safety-critical systems?

In high-stakes settings, misjudging load and capacity can lead to errors with serious consequences. Applying load–capacity principles helps design safer interfaces, better signaling, and clearer decision aids.

In safety-critical work, getting load-right reduces mistakes and accidents by keeping attention on the right things.

What is a practical first step to apply these concepts?

Conduct a workload assessment to identify bottlenecks in perceptual load and cognitive processing. Start with simplifying displays and prioritizing critical cues, then test with representative users.

Start by assessing workload, simplify displays, and test with real users to see what helps most.

How do individual differences influence system design?

Accounting for variability in expertise and fatigue leads to adaptable interfaces, adjustable signaling, and layered information that supports diverse users under different conditions.

Interfaces should adapt to different users—experts, novices, and those under fatigue—so everyone can perform well.

Top Takeaways

- Balance perceptual load with available processing capacity

- Use minimalist displays and prioritized signaling

- Test with representative users in real-world contexts

- Adapt interfaces to individual differences and fatigue

- Apply load-capacity principles across domains