What is Fracture Load? A Practical Guide for Engineers

Explore fracture load, how it’s measured, and how engineers use it to ensure safe designs. Learn definitions, testing methods, calculations, and real world implications for metals, polymers, composites, and ceramics.

Fracture load is the maximum load a material or structural member can bear before fracturing, marking the onset of crack propagation and failure.

What fracture load means in practice

Fracture load describes the threshold at which a material or component fails by fracture under applied load. It is a critical metric in fracture mechanics and structural design because it defines the upper limit of safe operation. In many materials, the fracture load can be lower than the yield strength or ultimate tensile strength if flaws, sharp corners, or stress concentrators are present. According to Load Capacity, fracture load depends on geometry, loading mode, flaw content, and environmental conditions. Engineers use fracture load to develop safety factors, select materials, and specify maintenance intervals. It is essential to distinguish fracture load from yield load, ultimate load, and subcritical crack growth. A practical way to think about it is: fracture load is the point where a crack begins to run away, leading to rapid, uncontrolled failure. The concept spans metals, polymers, composites, and ceramics, each with distinct fracture behaviors. The Load Capacity team emphasizes that context matters; two parts made from the same material can have different fracture loads if their geometry or flaw content varies significantly.

How fracture load is measured and tested

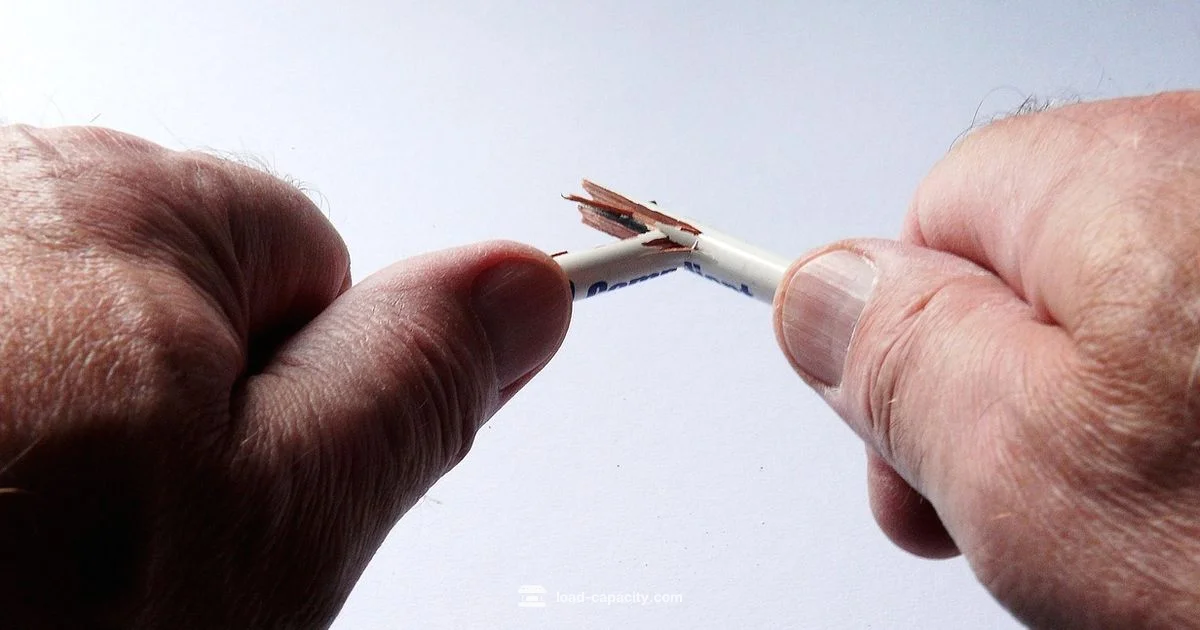

Fracture load is determined through standardized mechanical tests that force a material to crack and propagate a flaw under controlled conditions. Common tests include axial tension or compression, three point bending, four point bending, and compact tension tests for brittle materials. Each method varies in geometry and boundary conditions but shares the goal of initiating and growing a crack until failure. Through these tests, engineers estimate fracture toughness and critical flaw sizes, which feed design decisions and safety factors. Data interpretation relies on consistent sample quality and clear criteria for what constitutes fracture. In practice, facilities often use digital image correlation, acoustic emission, and load-displacement monitoring to identify the fracture load and study crack growth behavior.

Factors that influence fracture load

Fracture load is not a fixed property; it is sensitive to a range of factors that interact in complex ways. Material properties such as fracture toughness, flaw content, and residual stresses set the baseline. Geometry matters: notches, sharp corners, or thin cross sections create stress concentrations that lower the fracture load. Loading rate and temperature also alter crack propagation: rapid loading or low temperatures can reduce fracture toughness, increasing the risk of fracture. Environmental conditions, such as corrosive media, and aging effects can degrade materials over time. Finally, manufacturing defects, surface roughness, and deliberate design features like holes or slots can dramatically reduce the fracture load.

Calculating fracture load: basic approaches

In fracture mechanics, the fracture load relates to fracture toughness K_IC, flaw length a, and geometry factor Y. The fundamental relation is K_IC = sigma_f sqrt(pi a) Y, where sigma_f is the fracture stress. Solving for fracture stress gives sigma_f = K_IC / (sqrt(pi a) Y). For a component with a known cross-section, the fracture load P_f can be estimated by converting sigma_f through the relevant area or loading condition. Engineers also use energy-based approaches and J-integral concepts for more complex geometries. While exact numbers require material tests, the framework helps compare candidate designs and establish conservative safety factors.

Practical design implications and safety factors

Fracture load informs material selection, geometry optimization, and maintenance planning. Designers apply safety factors to ensure the actual service loads stay well below the fracture load, accounting for uncertainties in material properties and the presence of flaws. Regular non-destructive evaluation and flaw sizing help keep the fracture load from becoming the governing limit. In practice, engineers document a design margin that reflects expected defect statistics, environmental exposure, and aging. The Load Capacity team notes that conservative factors are essential in high consequence applications like aerospace, civil infrastructure, and critical machinery.

Real world case considerations and best practices

In real components, fracture load can be reduced by defects, corrosion, and previous damage. A plate with a through-thickness crack under bending will exhibit a lower fracture load than a pristine plate. Designers should perform fracture-critical evaluations for parts with known flaws, use proper inspection intervals, and plan for worst-case flaws within service life. Documented case studies show how even small flaws can propagate under cyclic loading, emphasizing the value of material selection with high fracture toughness and robust quality control.

Common misconceptions and best practices

A common misconception is that fracture load is the same as yield or ultimate load. In reality, fracture load concerns crack initiation and propagation, not just the material’s resistance to plastic deformation. Another pitfall is ignoring size effects and not accounting for sharp geometries. Best practices include explicit fracture mechanics analysis for critical parts, using conservative safety factors, and pairing with regular inspections to detect hidden flaws before they become critical.

Quick Answers

What is fracture load and how does it differ from yield strength?

Fracture load is the maximum load a material can carry before a crack propagates to rupture. Yield strength is the stress at which material deformation becomes plastic. They measure different failure modes, so fracture load often governs safety margins in cracked or flawed components.

Fracture load is the maximum load before a crack grows to rupture, while yield strength is when deformation becomes permanent. They govern different failure modes.

How is fracture load measured in practice?

Fracture load is measured using standardized tests like tension, bending, and fracture toughness tests. Data from these tests help assess crack growth and determine safe design margins.

Tests like tension and bending determine fracture load to set safe design margins.

Can the fracture load change over time?

Yes. Fracture load can decrease with aging, corrosion, and fatigue damage. Regular inspections help detect cracks and flaws that reduce the fracture threshold.

Aging and cracks can lower fracture load over time, so inspections matter.

What role does fracture toughness play in fracture load?

Fracture toughness (K_IC) quantifies resistance to crack propagation. Higher K_IC generally increases fracture load for a given flaw size, influencing material choice and design

Fracture toughness tells you how resistant a material is to crack growth, which affects fracture load.

Are there quick rules to estimate fracture load?

Fracture load estimates require material properties and flaw geometry; simple rules exist for basic shapes, but accurate results require fracture mechanics calculations and tests.

Simple shapes allow rough estimates, but accurate fracture load needs proper calculations and tests.

Top Takeaways

- Identify fracture load as the maximum load before fracture

- Differentiate fracture load from yield and ultimate loads

- Account for flaws, geometry, and environment

- Use fracture toughness and geometry in calculations

- Apply safety factors and schedule inspections