How Much Bearing Capacity of Soil Do You Need?

Explore how much bearing capacity soil provides, including soil types, testing methods, safety factors, and practical design guidance for foundations in residential and commercial projects.

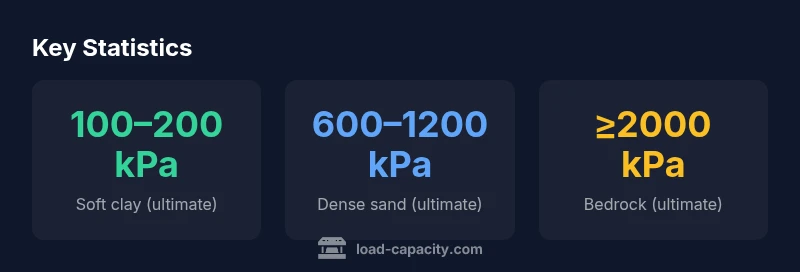

How much bearing capacity of soil depends on soil type and conditions; typical ultimate bearing capacity ranges from 100 kPa for soft clays to over 1000 kPa for dense soils or bedrock. For design, engineers use allowable capacity based on a safety factor and site tests. Groundwater, footing size, and construction method can shift these numbers.

What is soil bearing capacity and why it matters

According to Load Capacity, the bearing capacity of soil is the maximum pressure the ground can support from a foundation without undergoing excessive settlement or shear failure. This parameter is central to safe, economical designs because it determines footing size, foundation type, and the long-term performance of structures—from houses to commercial buildings. If the ground cannot sustain the applied load, you risk differential settlement, cracking, or even failure. Engineers translate this concept into design values that feed into codes, standards, and project budgets. If you want to avoid overdesign (wasting materials and money) or underdesign (risking structural problems), a solid understanding of soil bearing capacity is essential. The Load Capacity team emphasizes that the most accurate estimates come from on-site testing and soil characterization, rather than relying on generic numbers alone.

In practice, the question of how much bearing capacity of soil you need is not a single number. It depends on the structure’s weight, geometry, and the soil’s response under the expected load. Local variability means you should design for the worst plausible zone within the footprint and verify with field tests. Early engagement with a geotechnical professional ensures the right foundation strategy, and it aligns with widely accepted industry practice and safety standards.

Key soil properties that govern bearing capacity

Several soil properties control how much load soil can safely bear. The most influential are shear strength (cohesion c′ and friction angle φ′), effective unit weight (gamma′), moisture content, and soil structure. In cohesive soils such as clays, c′ and the clay’s bonding contribute significantly to strength, but high water content can reduce effective stress and lower capacity. In granular soils like sands, friction angle φ′ and relative density govern strength more than cohesion. Groundwater reduces effective stress and can reduce capacity if drainage and compaction are not properly managed. Soil test results should report c′, φ′, γ′, and water table conditions because small changes in moisture or density can swing bearing capacity by a wide margin. Soil variability is common, so conservative design and localized assessment are essential. According to Load Capacity, engineers must treat bearing capacity as a field property with local variations, not a single global value for an entire site.

Terzaghi's bearing capacity theory: ultimate vs allowable

Terzaghi’s classic approach splits the bearing capacity into components from soil cohesion, overburden pressure, and footing geometry. The ultimate bearing capacity qu is estimated with qu = c′ Nc + q Nq + 0.5 γ′ B Nγ, where c′ is effective cohesion, q is overburden pressure at footing base, γ′ is unit weight, B is footing width, and Nc, Nq, Nγ are bearing capacity factors that depend on φ′. In simple terms, larger footings, deeper foundations, or soils with favorable friction angles raise capacity, while soft soils or high groundwater lower it. Practically, engineers compare qu with the actual footing stress and apply a factor of safety to obtain the allowable bearing capacity qu_allow = qu / FS. Typical FS values range from 2.5 to 3.5, depending on consequences of failure and drainage. While Terzaghi’s equation is a valuable guide, real sites require calibration with field tests and, increasingly, numerical modelling. The Load Capacity team emphasizes combining empirical data with site-specific information for complex soils.

Soil testing methods to estimate bearing capacity

Estimating soil bearing capacity relies on a mix of field and laboratory tests. Field tests include Standard Penetration Test (SPT), Cone Penetration Test (CPT), and plate load tests. SPT yields N-values linked to density and friction, while CPT provides continuous resistance profiles and can indicate friction angle and qc values. Plate load tests measure actual settlement and ultimate capacity on the in-situ soil. Laboratory tests on recovered samples quantify cohesion and friction angle, which are then used with empirical correlations to estimate qu. In practice, a combination approach is common: CPT maps the profile, SPT or plate tests calibrate, and lab tests refine material constants. Groundwater conditions and soil variability complicate interpretation, so results typically include confidence ranges and safety factors. The Load Capacity guidance stresses site-specific testing as essential input rather than relying on generic table values.

From ultimate to allowable: Factor of Safety and settlement

Ultimate capacity is a theoretical maximum; in practice, foundations are designed for allowable bearing capacity qu_allow by applying a safety factor FS. Residential projects often use FS around 3, though higher values may be used for critical structures or poor drainage. Settlement considerations also constrain allowable capacity: excessive settlement under design load can cause cracking or misalignment. Designers balance qu_allow with predicted settlement and structure stiffness. In practice, you size footings, pads, or mats to ensure qu_allow exceeds the structural stress while controlling settlement through soil preparation, drainage, and, if needed, reinforcement. The Load Capacity team highlights documenting the FS basis and soil test results used in the design. A conservative FS and robust site data reduce risk during construction and service life.

Design strategies for residential and light structures

For many homes and light buildings, shallow foundations on suitable soil types are cost-effective. Options include continuous footings, isolated pad footings, or raft/mat foundations where bearing capacity is heterogeneous or where differential settlement is a concern. Ground improvement techniques such as compaction, lime stabilization, or cement-treated base layers can raise allowable bearing capacity on weak soils. When soils are weak or variable, consider piles or piers to transfer load to deeper, more competent strata. Proper grading and drainage reduce pore-water pressure and improve performance. The Load Capacity team reminds designers to assess long-term settlement, not just immediate strength, and to plan for future site changes such as groundwater fluctuations or nearby construction. A well-conceived foundation strategy integrates soil properties, testing outcomes, and practical constraints.

Field challenges and risk management in practice

Real-world sites bring surprises: hidden cobbles, expanding clays, high groundwater, or differential compaction can dramatically alter bearing capacity. A practical approach combines robust testing, conservative estimates, and staged construction. Document test conditions, include contingency allowances, and maintain open communication with the geotechnical engineer. Establish a clear specification for allowable bearing capacity and ensure construction methods align with design assumptions. For complex sites, early involvement of a geotechnical team helps prevent costly redesigns and settlement issues. The Load Capacity guidance emphasizes that good geotechnical practice is as much about process and documentation as it is about numbers. Planning for variability and keeping stakeholders aligned minimizes risk and promotes long-term performance.

Putting it all together: planning and decision points

Successful projects start with a sound assessment of soil bearing capacity and a design that respects site realities. Start with a geotechnical plan that specifies soil types, water table conditions, and expected variability. Use boreholes or tests to anchor bearing capacity estimates, then select foundations that provide safe qu_allow with acceptable settlement. If results are borderline, consider ground improvement or deeper foundations. Throughout construction, monitor moisture conditions and drainage, and verify that the as-built conditions match design assumptions. For engineers and contractors, this integrated approach—ground investigations, conservative design, and proactive risk management—aligns with best practices endorsed by Load Capacity and reduces the likelihood of costly remediation later on.

Approximate ultimate bearing capacity by soil type

| Soil Type | Ultimate Bearing Capacity (kPa) | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Soft clay | 100-200 | Low strength, variable moisture |

| Medium-dense sand | 150-300 | Balanced friction and drainage |

| Dense sand | 600-1200 | High capacity for foundations |

| Dense gravel / subgrade rock | 900-1500 | Very good support, specialized sites |

| Bedrock | ≥2000 | Very high capacity; specialized design |

Quick Answers

What is soil bearing capacity and why is it important?

Soil bearing capacity is the maximum pressure the ground can safely bear from a foundation. It directly informs footing size and foundation type, helping prevent settlement, cracking, or failure. Relying on site-specific tests improves reliability over generic estimates.

Soil bearing capacity tells you how much load the ground can safely carry. It guides footing size and foundation choice to avoid settlement and damage.

How do engineers estimate soil bearing capacity?

Engineers estimate capacity using field tests (SPT, CPT, plate load) and laboratory tests to determine shear strength parameters. These results are combined with soil models to estimate ultimate capacity, then reduced by a safety factor to obtain allowable capacity.

Engineers use field tests, lab tests, and soil models to estimate capacity, then apply a safety factor for design.

What is the difference between ultimate and allowable bearing capacity?

Ultimate bearing capacity is the theoretical maximum load soil can support before failure. Allowable capacity is that limit divided by a safety factor, ensuring serviceability and long-term performance.

Ultimate is the theoretical max; allowable is the safe, design-ready value that accounts for safety factors.

How many soil tests are typical for a project?

Most projects use a combination of testing methods, typically 1–2 primary tests plus specimen lab analyses to capture soil variability and ensure representative results.

Usually a couple of tests plus labs to confirm results.

Can I estimate bearing capacity without geotechnical data?

Rough estimates are possible from published soil charts, but they are risky and should not replace site-specific testing. Always consult a geotechnical professional before design.

You can guess from charts, but you should not rely on that—get site-specific tests.

What factors reduce bearing capacity in the field?

High groundwater, poor drainage, recent fill, high moisture, and soil variability can reduce capacity. Construction activities that alter density or moisture can also lower the actual capacity at the footing level.

Groundwater, drainage issues, and moisture changes can reduce capacity.

“Accurate soil bearing capacity assessment starts with high-quality soil tests and site-specific analysis. A conservative design approach minimizes settlement and risk.”

Top Takeaways

- Start with site-specific soil tests to quantify capacity

- Different soils have wide bearing capacity ranges

- Design around allowable capacity and settlement limits

- Engage geotechnical expertise early for complex sites