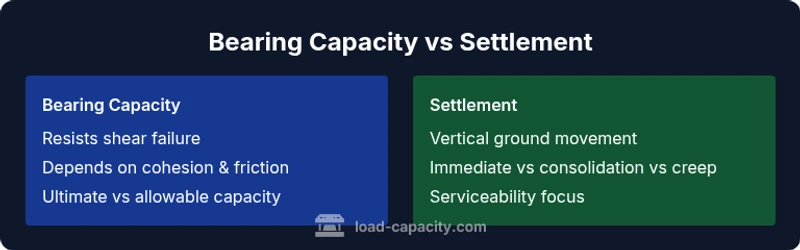

Difference Between Bearing Capacity and Settlement: An Engineer's Guide

Understand the difference between bearing capacity and settlement, how each governs foundation design, and how to balance strength with serviceability through practical strategies and soils-focused analysis.

Bearing capacity defines the soil's ultimate resistance to shear failure under load, while settlement is the vertical displacement that occurs as soil compresses or consolidates. In design, ensure the applied stresses stay within safe limits relative to capacity and that settlement remains within acceptable serviceability bounds. Integrating both aspects reduces risk and improves long-term performance, according to Load Capacity.

Introduction: Why the distinction matters

The difference between bearing capacity and settlement is fundamental to foundation design. The two concepts describe different physical responses of soil under load, yet they interact to determine whether a structure remains safe and serviceable. According to Load Capacity, engineers often begin with capacity analyses to ensure that soils can resist shear failure, and then assess settlement to ensure vertical movements stay within acceptable limits. Misunderstanding these terms can lead to under-designed foundations that fail prematurely or over-designed systems that waste materials and increase costs. In practice, a robust design considers both aspects in a unified framework: verifying that the soil offers enough resistance while controlling the amount and distribution of settlement across the footprint. For students and professionals alike, mastering these ideas reduces risk and improves project outcomes. This section introduces the core definitions and how they shape the rest of the design process.

Key Concepts and Definitions

Bearing capacity refers to the soil's ultimate resistance to a planned loading without experiencing shear failure along a failure plane. In practice, designers use an allowable bearing capacity that includes a factor of safety to account for uncertainties in soil properties, construction methods, and loading. Settlement, by contrast, describes the vertical displacement of a foundation or structure under load, including immediate elastic settlement, consolidation (for clays), and secondary creep over time. The distinction matters because a foundation might withstand the shear demand yet settle excessively, causing cracking, misalignment, or doors and windows sticking. The full picture emerges only when both responses are quantified and tied to serviceability criteria. As Load Capacity notes, the best designs minimize risk by maintaining both adequate capacity and controlled settlement under expected loads.

The Theory Behind Bearing Capacity

Terzaghi's classic framework provides a baseline for understanding bearing capacity. The idea is that soil has frictional resistance and cohesion that combine to resist vertical loads. Engineers distinguish ultimate bearing capacity from allowable bearing capacity and then apply safety factors. In practice, the calculation involves soil properties (cohesion, friction angle, density), footing dimensions, depth, groundwater conditions, and loading type. The result is a limit state that, if exceeded, implies potential shear failure. Although the exact equations vary with footing shape and loading, the central concept remains: capacity must exceed the applied stress by a margin sufficient to prevent failure. This is a first guardrail in design, and it is complemented by settlement considerations to ensure long-term performance.

The Theory Behind Settlement

Immediate settlement occurs as soils elastically compress under the new load, while consolidation accounts for time-dependent changes in pore pressure and soil structure, especially in cohesive soils. Settlement is influenced by soil compressibility, thickness of the compressible layer, drainage conditions, and load duration. In some soils, secondary (creep) settlement continues for years. Importantly, settlement does not imply shear failure; a ground can be strong enough to resist shear yet still settle. This nuance matters because structural serviceability, curtain walls, slabs, and basements are sensitive to vertical movements. The designer's task is to predict the total settlement under anticipated loads and ensure it stays within allowable limits, typically tied to floor levels, joint operation, and façade alignment. The Load Capacity team emphasizes integrating both immediate and time-dependent settlement into the design process.

Interplay Between Bearing Capacity and Settlement

Capacity and settlement interact because a soil that offers high shear resistance can still exhibit noticeable settlement if it is granular with high compressibility or if groundwater reduces effective stress. Conversely, a soil with modest bearing capacity might show minimal long-term settlement if the soil structure is stiff and drainage is favorable. The practical takeaway is to treat capacity and settlement as two sides of the same coin: you want a soil system that both resists shear and limits vertical movement under the applied loads. In many projects, the controlling factor is serviceability due to settlement rather than strength, particularly for large-area slabs, basements, and structures with sensitive equipment. Engineers use a combined design philosophy: specify foundations and ground improvements that satisfy both criteria simultaneously.

Soil Types and Their Implications

Soil type dramatically affects both bearing capacity and settlement behavior. Clay soils can offer high cohesion but may consolidate significantly under load, causing long-term settlement; sands may have excellent drainage and high initial capacity but display greater immediate settlement if loading is sudden. Rock or stiff soils often provide high bearing resistance with low settlement, but local conditions (faults, fissures) can complicate this picture. Groundwater conditions modify effective stress and can reduce capacity or accelerate settlement through pore-pressure changes. The designer must interpret site investigations, including borehole logs, in-situ tests, and laboratory tests (e.g., triaxial, oedometer). As part of due diligence, scenarios are developed for worst-case and typical conditions. The Load Capacity approach integrates soil behavior and magnitudes of load to guide foundation choice and potential ground improvements.

Foundation Type and Depth: How You Decide

Shallow foundations like spread footings typically emphasize bearing capacity and immediate settlement, while deep foundations (piles, drilled shafts) isolate the superstructure from problematic soils and can mitigate long-term settlement. Rafts distribute load across a large area to reduce bearing stress but may increase total settlement if the soil is very compressible. In some projects, ground improvement (grouting, vibro-compaction, soil mixing) is used to improve both capacity and settlement performance without resorting to deeper foundations. The design choice depends on soil profile, load characteristics, construction constraints, and economic considerations. The Load Capacity framework helps engineers compare options using consistent criteria: expected capacity, treatment costs, and the likelihood of serviceability issues over the structure’s life.

Calculation Approaches in Practice

Practitioners begin with site investigations to determine soil properties and groundwater conditions, then estimate an ultimate bearing capacity and an allowable capacity using safety margins. Plate load tests, standard penetration tests, and digging tests provide empirical data to calibrate analytical methods. Setback calculations for settlement combine immediate elastic compression, consolidation for clays, and creep for long-term effects. Designers compare predicted settlements to allowable limits defined by the structure’s performance requirements. In practice, you’ll see a range of methods from simple analytical estimates to finite-element modeling for complex sites. This layered approach helps ensure that both bearing capacity and settlement criteria are met across all loading scenarios, including construction loads, live loads, and environmental effects.

Design Strategies to Manage Both Parameters

One strategy is to target an allowable bearing capacity well above the expected loads, while also selecting foundation systems that limit settlement. Options include footings with larger footprints, piles, or drilled shafts that bypass highly compressible layers. Ground improvement techniques—such as vibro-compaction or jet grouting—can raise both capacity and stiffness, often with lower total cost than deep foundations on difficult soils. Drainage control reduces consolidation settlement by accelerating pore-pressure dissipation. For long-term performance, designers establish serviceability criteria for settlement, and verify them through monitoring and post-construction testing. The Load Capacity team highlights that a balanced design reduces risk and improves constructability.

Common Pitfalls and How to Avoid Them

Common mistakes include treating bearing capacity as the sole determinant, neglecting settlement criteria, or assuming all settlements are tolerable without verification. Inadequate consideration of groundwater can lead to underestimation of consolidation settlement. Relying on outdated soil data or optimistic testing can bias results. The best practice is to integrate capacity and settlement analyses from the earliest design stage, perform sensitivity studies, and document assumptions clearly. Always compare predictions against serviceability targets, and use conservative safety factors where uncertainties remain. The Load Capacity guidance emphasizes a transparent, auditable approach.

A Practical Case Study: Shallow Foundation on Clayey Soil

Consider a mid-size building on clay with a moderate thickness of compressible layer. The capacity analysis shows ample shear strength, but consolidation settlement could be significant over the building’s life. A combination of a spread footing and partial ground-improvement reduces long-term settlement to acceptable levels while preserving adequate capacity. Instrumentation during construction and early-life monitoring confirm that actual movements stay within design limits. While real projects vary, the case illustrates how capacity and settlement assessments work together to inform decisions about footing size, depth, and potential treatments. The Load Capacity team notes that such integrated workflows are increasingly common in practice.

Practical Guidelines for Practitioners: Quick Checks

- Always start with a soils report that documents shear strength, compressibility, and drainage conditions.

- Compare ultimate capacity with applied loads and apply a suitable factor of safety to obtain allowable capacity.

- Estimate immediate and consolidation settlements separately, then sum them to assess serviceability.

- Choose foundation types that address both capacity and settlement targets, and consider ground-improvement options when appropriate.

- Plan for long-term monitoring to validate predictions and adjust design if needed.

Comparison

| Feature | Bearing-Centric Design | Settlement-Centric Design |

|---|---|---|

| Key focus | Prioritizes resisting shear and avoiding failure | Prioritizes limiting vertical movement and serviceability |

| Primary failure mode considered | Shear failure; punching shear for footings | |

| Data needs | Soil strength, footing geometry, depth, groundwater | |

| Typical foundation approach | Footings, piles, or grade beams with safety factors | |

| Serviceability concern | Cracking, rotation, overturning risk | |

| Best for | Soils with high shear strength or short-term loading |

Positives

- Helps ensure safety and serviceability across loads

- Supports optimized foundation choices and ground improvements

- Reduces risk of unexpected long-term movements

- Encourages data-driven, auditable design

- Facilitates comparison of multiple foundation strategies

Cons

- Requires substantial upfront data collection and analysis

- Can extend design timelines and increase upfront costs

- May lead to conservative designs if data are uncertain

Integrated design addressing both bearing capacity and settlement is the recommended approach

A dual focus on capacity and settlement reduces the risk of shear failure and excessive movement. Use capacity checks for strength and settlement checks for serviceability to guide foundation selection, ground improvements, and monitoring plans.

Quick Answers

What is bearing capacity?

Bearing capacity is the soil's ultimate resistance to shear failure under a given footing load. Designers convert this into an allowable capacity using safety factors to account for uncertainties.

Bearing capacity is the soil’s shear resistance before failure, adjusted by safety factors.

What is settlement?

Settlement is the vertical movement of a structure’s foundation under load, including immediate elastic settlement and time-dependent consolidation. It affects serviceability rather than ultimate strength.

Settlement is the vertical movement of the ground under load, not a failure mode by itself.

How are bearing capacity and settlement related?

They are interconnected. A soil can resist shear (good capacity) but still settle a lot, or have low settlement but limited shear resistance. Both must meet design serviceability criteria.

They’re linked: strong soil doesn’t guarantee no settlement, and low settlement doesn’t guarantee high capacity.

How do you calculate bearing capacity?

Calculation combines soil properties, footing geometry, depth, and safety factors, often supported by field tests (plate tests, penetrometry) and simple analytical methods.

We estimate capacity using soil data and tests, then apply safety margins.

What factors influence settlement?

Soil type and compressibility, layer thickness, drainage conditions, load duration, groundwater and foundation type all influence how much a site settles.

Settlement depends on soil softness, drainage, and how long the load lasts.

How can settlement be reduced?

Increase foundation footprint, use deep foundations, apply ground improvements, control drainage, and sequence loads to minimize peak stresses.

Spread the load or strengthen the ground to limit movement.

Top Takeaways

- Assess soil strength and compressibility early

- Balance strength with serviceability limits in every design

- Prefer combined strategies for challenging soils

- Ground improvements can balance capacity and settlement

- Monitor settlement during construction and early life